Megan Smith Göttsches

School of Language, Culture and World Affairs, College of Charleston, USA

Introduction

Over two decades of violent conflict has taken its toll on northern Uganda. As the people of the region attempt to resettle in this post-conflict landscape, changes in attitude and activities have become apparent. Women who lost their husbands during the conflict returned home to find a new host of problems such as loss of land and social support which they must overcome in order to generate livelihoods and pursue a life which they deem respectable.

This paper focuses on a group of widows situated in villages around a disbanded internal displacement camp in northern Uganda and how their actions and attitudes towards their subsuming traditionally male roles while intensifying their own gender’s roles has been helpful in their ability to participate in livelihood activities. The women at the heart of this study were married prior to the conflict’s escalation and lost their husbands during the conflict and internal displacement period (1986-2006). Through loosely applying the capability approach and theoretical concepts surrounding it, a clearer picture is created explaining how the relationship between the actions and choices of these women helps them achieve a form of well-being which they deem relevant and important. According to Doss et al. (2012: 598), “land is the most important asset in rural Uganda. Land rights and ownership are embedded deeply in social norms and customary law, including those related to marriage and inheritance”. Consequentially, the systems which dictate land rights and ownership fell under immense pressure as the conflict ruptured both cultural practices and family units. This puts women, along with children, the disabled and the elderly at risk as they find themselves in vulnerable and unsecure positions within society. For women, this is especially precarious as “women’s land rights’ vulnerability under custom is exacerbated by the inherent fact of women’s transience: women move from their maiden families to their marital homes (or cohabiting homes) and sometimes back again to their maiden homes. … Should her husband or in-laws become unsupportive, she will lack the protection she needs to claim her property rights” (Adoko et al. 2011: 3). Widows tend to find themselves in this position when social systems become challenged in the aftermath of conflict, and understanding the dynamics of women and land access in a post conflict setting is crucial not only to interpreting potential role renegotiation and livelihood activities which lead to perceived successes, it is also pertinent for the understanding of the land and livelihood insecurities of the region on a larger scale.

1. Background and Theoretical Framework

Conflict is a mainstay in humanity. History has been marred by it and the future will continue to experience both it and its catalytic effects on change in society. More often than not, groups who may outnumber those perpetrating the violence but are deemed ‘vulnerable’ (Carpenter 2005; GoU/PRDP 2006), such as women, children, orphans, the disabled and the elderly, find themselves irreversibly changed by conflict. Whether it is due to physical injury, emotional trauma, the loss of family or the loss of livelihoods, these groups feel these side effects of war more acutely than those of other actors perpetrating and fighting in the conflict. Ironically, the reshuffling of society during conflict creates an opportunity where the gender balance can be addressed (Afshar & Eade 2004; Klein & Wallner 2004; Moser & Clark 2001; Sweetman 2005; Turshen et al. 2002).

On no other continent in the world is this more true than in Africa. The patriarchal societies so common in countries across the continent experience a shift during conflict in which women are paradoxically empowered by the violence. However, this shift tends to be short-lived as, during the post-conflict period, the attempt to shift back to the status quo present prior to conflict is deeply felt.

“Though Africa has had more than its fair share of conflicts, especially the intrastate conflicts that followed the end of the Cold War, conflicts offer an opportunity, especially in the post conflict period, to redress the gender bias. Periods of post conflict peace building offer a fresh start for ensuring that a more gender sensitive world is created. Evidences show that in the main, though women make substantial gains during conflicts/crisis periods by acquiring new roles and behaviours, these are largely reversed in the post conflict period.” (Meintjes et al. 2001).

Despite the economic advantages and incentives created by women who are caught in this reconstruction of gender roles during conflict, the tendency of the patriarchal society still persists to rescind the conflict induced independence from women even if the woman’s overtures were productive.

In northern Uganda during the conflict between the Lord’s Resistance Army and the Government of Uganda (1986-2006), the people of Acholiland experienced internal displacement on a massive scale which left issues surrounding land in limbo and devastated cultural and traditional practices. With the return of ‘relative peace’ and resettlement (since 2007/08), widows tend to find themselves in a particularly precarious situation because, as in many African patriarchal societies, their access to land and securing a livelihood in the rural setting is contingent upon the marital relationship (Dolan 2009; Finnström 2003; Otiso 2006; Potash 1986; Tripp 2004) In Acholi culture, a widow, especially if she is a mother to the deceased husband’s children, is granted protection and secured land from her in-laws. This system was put under severe duress during the conflict (as were other cultural institutions such as informal education, traditional arbitration, etc.), and in most cases since the conflict has ended, land-grabbing and disputes have compounded the marginalization of widows. When possible, remarrying or participating in a levirate relationship (see Potash 1986) would seem like the most logical (and culturally less abrasive) way to secure access to land and livelihood.

However, even notions of being married and the cultural backing in its legitimization experienced pressure as well. A widow who was married prior to the conflict, with a negotiated bride-wealth and physical exchange of person from the natal to the husband’s household in observance by and up to the standard of the communities’ expectations, has a distinct level of security when it comes to land. This security is made greater if she has children. This isn’t to say that in the pre-conflict setting there were no land security issues; however, the fabric of society was stronger in the pre-conflict setting and specific cultural institutions regarding widows and their rights to land were upheld by a structured society. During the conflict and internment in the camps, this structure became non-existent. Institutions which dictated social norms suffered greatly because of the physical nature of the camps; communities were divided and living situations did not reflect the orderly socio-cultural norms of life prior to the conflict. Being interned doesn’t preclude the ability to get married; but it does make the enforcement of social institutions which should have been secured through bride-wealth and the physical transfer of a person from one homestead to another, difficult. Crowded camps did not have plots of land to farm. Oftentimes, people would trek during the day (when conditions permitted) to farm their lands, but they were not present on their land all the time. Return during the end of the conflict proved chaotic as land grabbing prevailed; but, threads of that strong social fabric still existed and widows who had been married prior to the war, though their space was more contested than ever during the return, still held rights to their husband’s land. In contrast, it could be assumed that those women who had married during their internment found it more difficult, if not simply impossible, to exercise their rights to land as widows because of the ineffectual nature of social institutions during internment.[2]

Women with dependents who were married prior to the war, widowed by the war and did not remarry, are the women that this case study followed. The study looks at the actions of these women from the perspective of capabilities. This is important because formulating a better understanding of the actions of vulnerable demographics experiencing post-conflict can lend to more appropriately calibrated policies which can protect and encourage their development.

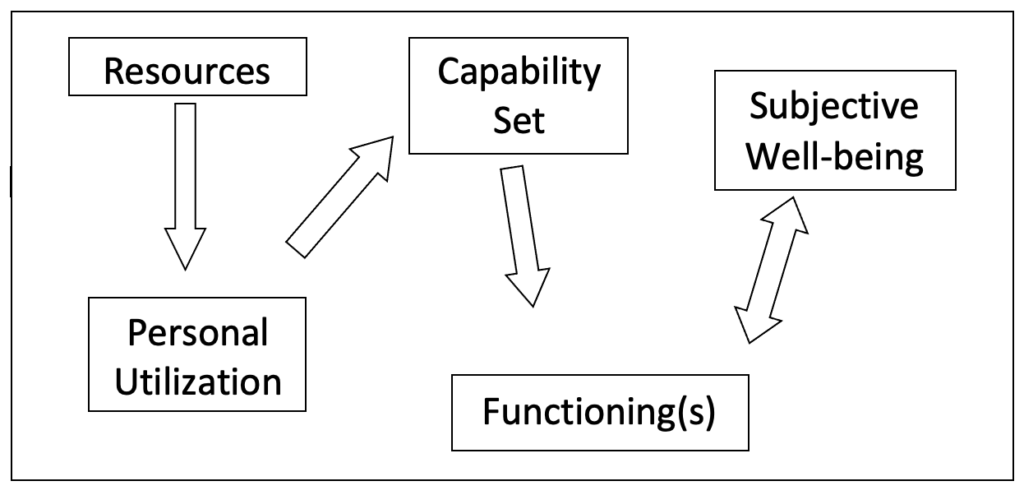

Using the Capability Approach (CA), an originally economics driven framework (see Sen 1984, 1995, 1999) which has been reworked and adapted to take on a more universalist (albeit still heavily rooted in economics) perspective (Nussbaum 1995, 2000), the conscientious decisions of these women cease to appear to be driven out of desperation. Contrarily, once these women are able to access land through either customary tenure, complex tenure[3] or through renegotiating access with their natal homes, they engage in livelihood activities with clear goals, expectations and methods through which they judge the success and failures of their endeavours. And they do this having made the decision not to have a male figurehead in their households. Using this as a starting point for other decisions these women make, examining how their livelihoods lead to subjective successes and whether or not their successes lead to a kind of confidence that would encourage these new roles over generations, is under consideration. Sen (1992) explains that “the well-being of a person can be seen in terms of the quality (the ‘well-ness’, as it were) of the person’s being. Living may be seen as consisting of a set of interrelated ‘functionings’ consisting of ‘beings’ and ‘doings’. A person’s achievements in this respect can be seen as the vector of his or her functionings. The relevant functionings can vary from such elementary things as being adequately nourished, being in a good health, avoiding escapable morbidity and premature mortality,” (Sen 1992: 39) – to being able to provide children with education or maintain a sound household. The research participants in question are able to engage in activities which lead to functionings that fulfill their own subjective intentions (see Box 1).

This case study seeks to elaborate on these women’ autonomous actions and intentions through the CA and compiled field data as well as explore their implications for the future.

Box 1: Basic Illustration of Elements and Interactions of the CA

Source: Adopted by author from Sen (1984, 1992, 1999) and Nussbaum (1995, 1999, 2000)

2. Research Questions

The situation explained above has specific consequences for women with dependents who were widowed by the war. This study, which seeks to examine their situation against a post-conflict backdrop through a CA lens, was conducted with the following questions in mind:

How do these women access land[4] in a post-conflict setting? It was assumed during the conflict that the breakdown of customary tenure would result in vulnerable demographics becoming landless and marginalized (see Adoko & Levine 2004). The scope and extent of this statement can be ascertained once it is understood if and how exactly these widows are able to access land.

Is there a link between gender role renegotiation and livelihood access? Discerning departures from or incorporated gender roles for the widows in question and how they utilize these roles to access livelihoods exemplifies the fruits of female agency. Their actions have specific intentions, that is, generating benefits from livelihood activities. Examining the relationship between the two entities over time will reveal how stated livelihood activities correlate with the women’s autonomous actions and assumption of gender roles. Another important factor is the extent to which the widows in question see their actions as a renegotiation where gender roles are concerned.

Is the utilization of land for livelihood activities successful and how do these women measure their success? Understanding how these women measure their successes and failures and the mechanisms which they utilize in order to achieve their goals ultimately reveals shifts in their perceptions and capabilities. Here, specific choices will be explored as their impact on the ability of these women to successfully participate in livelihood activities with their personal goals in mind has significant implications not simply for the family unit, but for their culture as well.

What are the social consequences of their renegotiation? Each of the previous questions has answers which will challenge notions of culture within the Acholi; women being able to hold on to their autonomy and be responsible for their own actions. Their capabilities and willingness to engage makes cultural shifts and changes palpable. The social consequences of their actions have an affect not only on their identities within the constructs of culture, but the way in which they teach younger generations as well.

Examining the correlation between renegotiating gender roles in a post conflict setting and how this negotiation leads to livelihood access which is both sustainable and secure can help scholars and policy makers alike understand the decisions made by women, their intentions and their expectations for the future. Employing the CA, which seeks to not only establish what an individual can do within the context of a set of circumstances but also to broaden the number and types of criteria examined to ascertain well-being, to the station and autonomous actions of these women will perhaps shed light and understanding on how and why they make certain choices.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study Area and Study Population

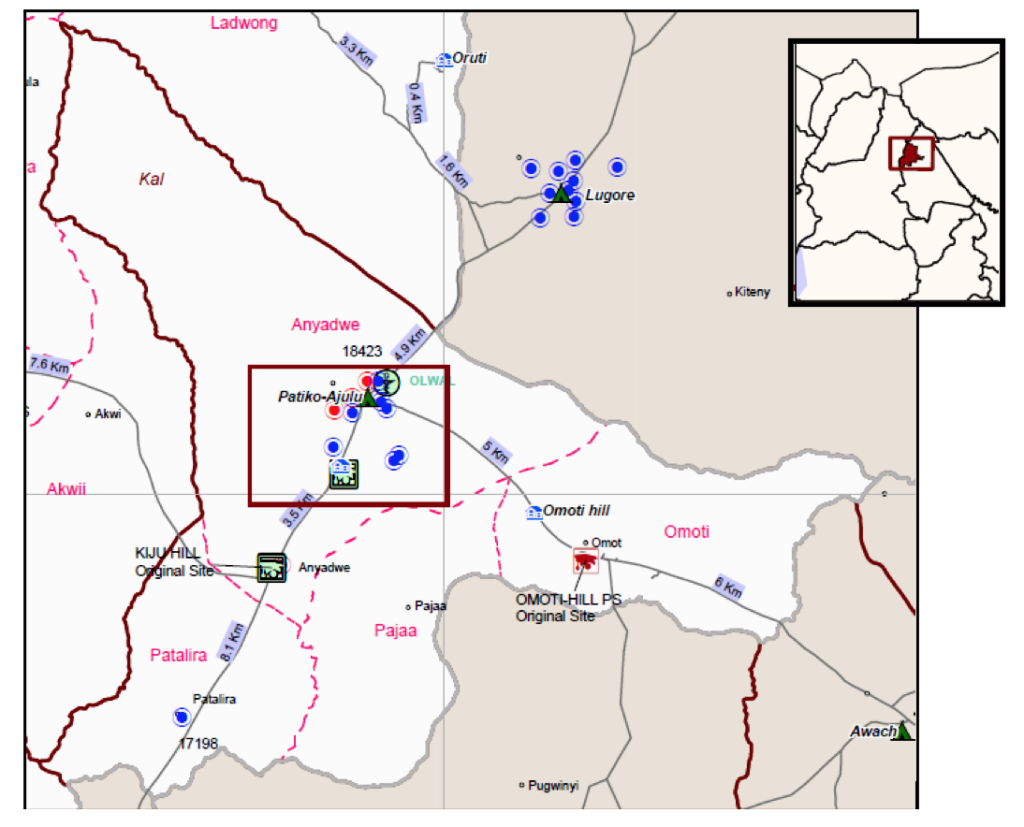

Patiko sub-county, located about 30km north of Gulu Municipality in northern Uganda provided a platform through which the research objectives could be explored as a case study where informants and information would be centralized as opposed to gathering data from throughout Gulu District at random.[5]

Patiko Sub-County lies at 3° 0′ 11″ North, 32° 20′ 39″ East and is part of Aswa County within Gulu District.

Map 1: Gulu District with Sub-counties (Study Area Starred)

Sources: UCC 2010 and CIA World Factbook 2012

At the end of 2005, the Patiko-Ajulu IDP camp was home to roughly 13,300 displaced individuals (GoU/Ministry of Health 2005: 44). As relative peace returned to northern Uganda and people began the return to their lands, many people chose to stay behind in IDP camps such as Patiko-Ajulu or they moved out towards the trading posts and less congested ‘satellite camps’, which were created to facilitate the resettlement process.

Patiko-Ajulu IDP camp was located in Kal Parish of Patiko Sub-county (see Map 2). The trading post south of the camp still serves as a central place of commerce for the surrounding villages. As of 2010, according to the District Camp Phase-out Committee, created by the Government of Uganda to facilitate the closure of remaining IDP camps throughout northern Uganda, only 910 inhabitants of the former Patiko-Ajulu Camp have remained in the same location (GoU 2010). The map below is an excerpt from an American Refugee Committee International survey which mapped the IDP camps in northern Uganda with the aid of data from major humanitarian organizations in 2007. The return process, even up until this point, has reimaged the landscape; the villages chosen to study are all part of Kal Parish. Omoti, Anyadwe, and Pajaa appear on the map but Pawel does not despite participants insisting its inclusion in Kal Parish. As such, Pawel was included in the study because of its proximity to the other villages while Patalira was excluded because of its remoteness[6]. However, the proximity of the four villages in question to the disbanded Patiko Ajulu IDP Camp provided a unique spatial and temporal unit which could be managed in a case study fashion.

Map 2: Kal Parish in Patiko Sub-county

Source: UNHCR 2007

The implementation of this research was completed within a two month period of time between February and April 2012. Several methodologies were employed to obtain both qualitative and quantitative data. As with any anthropological research, these methods and the way they were implemented were adjusted as circumstances demanded. Both the snowball sampling and random sampling methods were used to gather participants and informants who filled the criteria of the target population of the study and various forms of interviewing techniques and activities were carried out to gather data. Due to the potential sensitive nature of the discussions which would transpire with participants, it was necessary for the entire research team to be female; it was felt that having interviews and focus group discussions between women without men present would encourage them to be more ‘open’. Because of the characteristics of the data, the majority being qualitative in nature, the number of informants for that part of the study was limited to thirty, whereas with the quantitative side of the study, 97 informants participated in a short quantitative survey designed to give a substantial backdrop to the qualitative data. In addition to these methods, statistical data concerning populations and micro-finance access figures were gathered separately to provide a backdrop for the research.

3.2 Sample and Sampling Method

The participants needed for the qualitative interviews had to fit a specific parameter within society; that is, being widowed by the conflict. It was important for the study that the participants be able to offer a temporal perspective from the point of being a widow; therefore, only those women who were married prior to the beginning of the war and who lost their spouses during the conflict, and did not remarry, were considered. Narrowing the focus to a specific area in a case study fashion allowed for the use of snowball sampling for finding informants for the qualitative aspects of the study and the use of random sampling to interview informants for the quantitative aspects.

The target population, being single women above the age of thirty-five years with dependants who lost their spouses during the conflict, is defined by unique demographic constraints and was capped at thirty participants. In order to access these women, it was necessary to consult local council (LC) leaders who could identify the particular target population and, because of the relatively small populace of the case study area (4,300 inhabitants) whereby the informants would most likely be in contact with one another (Bernard 1994:97), it was only necessary for the LC to identify two or three targeted participants. Thus, by implementing snowball sampling with these women, they not only became mobilizers for the research, but they also helped populate the participant pool with others who fit the research criterion. It was also felt that, since the nature of the questions being asked during the study were specific, but not sensitive in nature, these women would not feel apprehension at identifying the next potential participant. The target population criteria were very important as these women would be able to give a temporal perspective to the research at hand. Therefore, relying on them to identify other participants who fit the demographic constraints was the best way to gather participants.

Systematic random sampling, in the loosest sense of the term, was utilized during the gathering of quantitative data; with a population of roughly 4,300 inhabitants spanning all age groups clustered together in four villages, the research team visited various homesteads within the villages. Systematic random sampling requires a sampling interval be designated and utilized to ensure uniformity (Bernard 1994: 82); however, the four villages in the case study area are significantly spread out and the villages themselves are not uniform in the manner which would be ideal for systematic random sampling. Care was taken to randomly choose homesteads to interview and ascertain relationships to previously interviewed households as to not duplicate surveys; the quantitative surveys were administered to one adult per homestead without regard to gender.

3.3 Data Collection Methods

The data collection methods included free listing, semi-structured interviews, quantitative surveys and focus group discussions.

The question at hand involving the sustainability of livelihood access through gender role renegotiation required several methodological approaches to gather the specific type of data needed to enrich the study. Gender role renegotiation in a conflict and post conflict setting is not a new phenomenon and can be physically seen in most cases (See Moser & Clark 2001; Sweetman 2005; Turshen 2002).

For the purpose of this study, a free-listing activity was employed during the interviews to see how women perceived and stated their gender roles and the roles of men over a temporal period spanning prior to the conflict up to the present. This activity was also duplicated to conceptualize the types of livelihoods these women accessed along the same temporal scale. Free-listing, according to DeMunck (2009), is helpful in identifying the cultural domain of a group of people; cultural domain being all things, at the same level of abstraction, that members of a culture or group say belong together. It is an emic category rather than etic because these things are shared and constructed by members of the group as opposed to outside societies (DeMunck 2009:47). By having the target population participate in free-listing activities concerning gender roles and livelihoods, it was intended that a correlation between the two categories would emerge over the temporal scale; that this activity might reveal a connection between the renegotiation which takes places and the types of livelihoods one accesses during a specific time period. Four time periods were specified for these free-listing activities; prior to conflict, during conflict, directly after conflict, and present.[7]

Semi-structured interviews were also initiated with all participants involved in the qualitative aspect of the study. These interviews were directed by an interview guide and conducted by an exclusively female research team to make the female participants more comfortable. The questions were intended to garner a more in-depth view of characteristics surrounding renegotiation and sustainable livelihood access. Participants were posed with direct questions regarding land access, income generating activities (IGAs) and livelihoods, social organizations and networks as well as gender role renegotiation, but also encouraged to expound upon issues they felt were important to them. Some were direct with their answers while others elaborated with life histories and anecdotal evidences; probing was used to encourage dialog and aid participants in “opening up” (Bernard 1994: 220).

The quantitative survey was completed to provide a backdrop for the qualitative data. The participants were chosen through systematic random sampling throughout the four villages in the research area. In total, 97 surveys were completed and compiled to provide a quantitative base for the qualitative data.[8] The questionnaires themselves comprised ten basic close-ended questions which corresponded with ideas developed during the semi-structured interview phase.

Two focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted during the course of the study with participants from the qualitative interviews based on their attitudes and answers to certain questions during the semi-structured interview process. The purpose of the discussions was to ascertain how these women perceive themselves as widows engaging in both gender roles and how they measure their success. Understanding whether or not engagement in these roles made them feel more secure and confident, thereby attributing to their livelihood access, were the main goals of these discussions.

4. Findings

In the following, the four research questions posed at the beginning of this study will be recapitulated and scrutinized by combining the processed data with the theoretical concepts inherent in the CA. This combination will be especially fruitful where autonomous actions which contradict cultural expectations and restrictions are concerned.

4.1 Accessing Land in a Post-Conflict Setting as a Widow

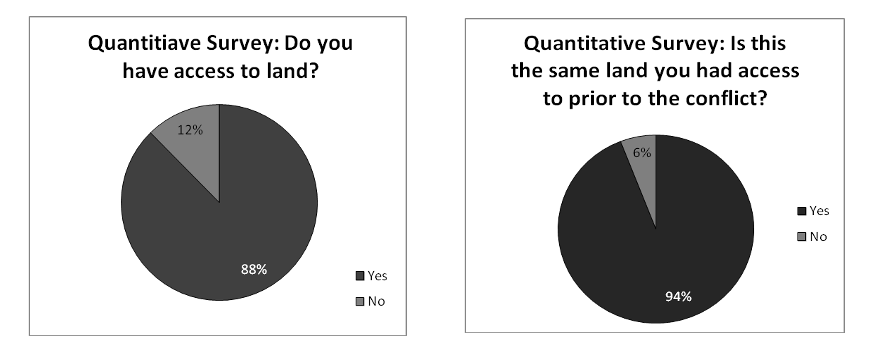

The breakdown of customary land tenure constructs is evident in the case study, though its degree is not as severe as one might have assumed it would be given the length of displacement (Benjamin & Fancy 1998). The quantitative survey revealed that 88 per cent of those interviewed have access to land and of that percentage, 94 per cent confirmed that it is in fact the same land they had access to prior to the war.

Graph 1 and Graph 2: Land Access and Tenure from Quantitative Interviews

Source: Goettsches Data Compilation (May 2012)

In the qualitative interviews, it was discerned that 64 per cent of the women questioned cited customary tenure (i.e. their deceased husband’s land) as their method of access, while 23 per cent cited ancestral tenure which entailed returning to their natal land. The 10 per cent citing complex tenure have been able to secure access via distant relatives; one participant claiming complex tenure explained that she was able to negotiate and utilize her deceased husband’s cousin’s mother’s land. This type of access may be more common than previously thought within the post-conflict context as families attempt to rebuild their lives. However the scope of this research could not afford a specialized examination of this phenomenon. As mentioned above, the distinction between access, ownership and user rights is beyond the parameters of this paper and so emphasis will be placed upon the ability of these women to access land more so than questions of security.

Graph 3: Negotiated Tenure Systems: Results from Qualitative Interviews

Source: Goettsches Data Compilation (May 2012)

Exercising the ability to negotiate methods of access which in the past had been underutilized (i.e. returning to the natal land) as well as navigate long established customary tenure practices despite land disputes is paramount to the livelihoods of these women. Aside from shifting gender roles to compensate for the lack of a male presence in a patriarch-dominant society, access to land in northern Uganda (and it could be said for the whole of rural Africa), is essential to achieving livelihoods and aspirations which they deem as relevant.

“… after the war, I lost my husband’s land to his brothers. They would not let me dig there. Now I beg land off my neighbours … Some space here and some there. I always lose and gain space … But it is not enough … I work hard here because children must go to school.” (Interview with participant 5, March 2012).

From a functionality perspective, the land which these women are able to farm is utilized for sustenance and, when in surplus, selling in the markets. However, their access to land is more complicated than providing consumable goods; they connect their utilization of land with their ability to send their children to school. The above quoted interview reveals one of many variations of the same idea which was elicited by enquiring about their ability to access and for what do they use the ‘fruits of their labour’. The consensus regarding accessing land and being able to provide the possibility for a better life for the next generation was overwhelming, both in the interviews and the focus group discussions.

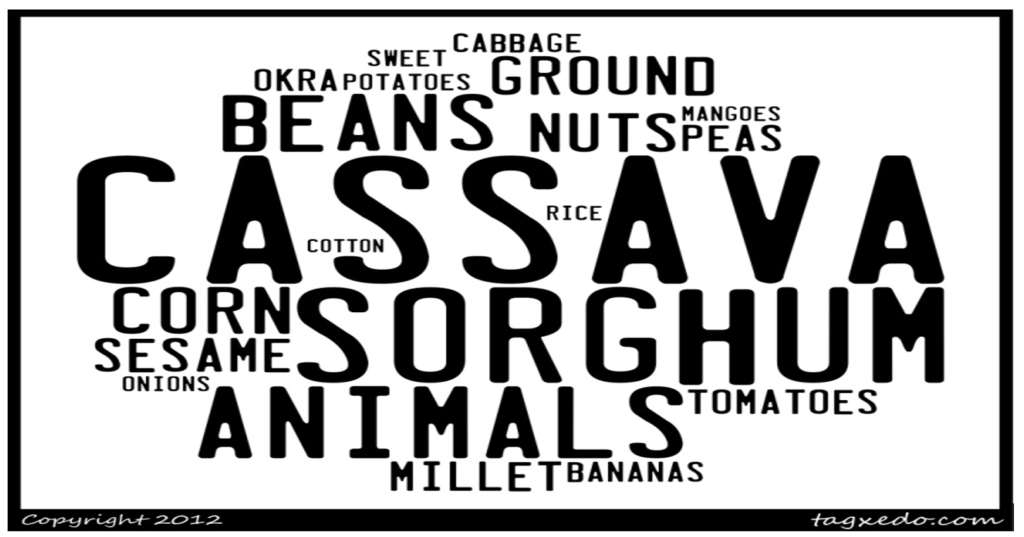

Image 1: A Visually Weighted List of Things Grown on the Land

Source: Goettsches Data Compilation (May 2012)

The visually weighted list above is the result of a free-listing exercise with the thirty participants of the qualitative interviews when asked to list how they utilize the land they access; cassava, sorghum and animals (husbandry) were most frequently mentioned while, for example, rice and cotton were less frequent. This makes sense as cotton isn’t consumable from a subsistence standpoint and rice is rather labour intensive. The commerce of these commodities in local markets exemplifies how important land access is in providing the basis for achieving their goals.

From a CA perspective, the components and relationships between land and widows can be broken down into manageable, albeit simplified, constructs. Land constitutes a resource which, because of human interaction and culturally placed significance, is invaluable. The manner in which widows are able to access this resource, whether it be via customary, ancestral or complex tenure avenues, and how they utilize the land (unanimously for farming and raising animals), comprises their personal utilization. The combination of these two factors leads to a specific capability set whereby questions of what they are actually able to do are emphasized. Here is where specific intentions and the actions leading to their realization can be observed; for example, forming aleya groups[9] to provide labour for farming. This then leads to the fulfillment of functionings which, as Sen explains, are “modes of being and doing” (Sen 1995:39). For these women, the functionings they wish to achieve concern being nourished, having a stable homestead and educating their children. These things cannot be achieved without farming as its provisions of both food and income are an integral part to achieving functionings they deem worthy of achieving. Accomplishing and sustaining these functionings leads to their perceived subjective well-being which is the sum of their functionings and the path taken to achieve them. The connection between accessing and utilizing land, and the functionings that can be achieved became apparent after extensive semi-structured interviews with participants:

“I do not have my own land, but I am allowed to dig my father’s land … what I plant, I sell and my home consumes. I am in an aleya group and a savings group. The aleya group helps me farm … the small profit I make, I put in the savings group. School fees are very high … when the children need school fees, I can use the money I save but sometimes it is not enough, so I rely on the savings group as well.” (Interview with participant 8, March 2012).

The above quote exemplifies an example of the actions of access and utilization and how they contribute to a functioning (in this case, sending children to school); it also exemplifies apparent shortcomings and methods to make up for them (in this case, not having enough profit for paying school fees, thus the need to rely on a borrowing system arises).

In the qualitative examination, 97 per cent of the women interviewed claimed they have access to land; meaning that they access, utilize and reap the benefits of accessing land. Despite this being a small case study, this number is significant given that previous research in conflict and post-conflict areas suggest that widows would be marginalized and hard pressed to find land access (see Berhane-Selassie 2008; Campbell 2005; Kamungi et al. 2005; Turshen et al. 2002).

4.2 Linking Gender Role Renegotiation and Livelihood Access

The relationship between gender roles and livelihood access is evidenced through the free listing exercises which took place with the participants as well as their explanations given during the qualitative component of the research. It is important to reiterate here that when the free listing exercise was being administered, we asked the participants to not just talk about their actions, but their actions along with the actions of those around them. The actions they listed for men varied between them referring to their own deceased husbands (usually noted by the participants when they focused on the ‘before’ and ‘during’ categories) and other men within their community. However, the free list concerning livelihood access was specifically meant for them to expound upon their personal actions. There are several factors about the visually weighted lists that render the data accurate from a historic perspective: firstly, the evidence of farming being a major component of everyday actions and livelihood access for all time periods except during the conflict where, despite their actions and small farming ventures around the camps and back home, the vast majority of people relied upon NGO aid as a livelihood access; and secondly, during their time in the camp, all participants claimed to have witnessed the disenfranchisement of men through alcohol and abuse which they reported in the exercise thus providing a relevant and realistic revelation of camp life which is both correlated and pervasive in literature pertaining to internal displacement and gender relations within conflict.

Table 1: Free Listing Frequencies Exemplified with Visually Weighted Lists[10]

The frequency with which each piece of information repeated itself was catalogued and then utilized to generate graphics which visually exemplified these frequencies in relation to each other through size. It is important to note that in freelisting exercises, the repetition of a theme or idea represents a type of collective knowledge; for this study in general, and this exercise in particular, the collective knowledge is important because it can reinforce or bolster historical evidences, or, when done temporally, it can show a shift in attitudes, perceptions and actions over time.

The appearances of aleya, small scale business ventures (SSBVs) and savings groups as practices women have partaken in since the conflict ended are significant and correlated with the types of livelihoods they access and if examined from a CA perspective, it is a distinct example of how actions have translated into functionings and contribute to subjective well-beings. However, these actions rarely appeared in the categories where we spoke of men’s actions; if they did appear, their frequencies were too insignificant to note. This begs the question of whether or not an actual renegotiation is happening or is the shift attributed to a general increase in responsibility and creative activities undertaken by these women to meet these responsibilities. There is a relationship between the actions of these women and their livelihoods, but other than their insistence that their farming activities have increased significantly to include tasks traditionally done by men (which in itself is incredibly significant and important to the female agency of these women and their food security) and the responsibility of school fees for children has shifted, their conviction that gender roles are in the process of changing was mixed. Some felt and expressed the opinion that things are not changing while others were adamant that the roles are changing because their perceptions of themselves within their current space and context suggests a type of empowerment and felt-independence, and others branded the change in roles as merely circumstantial as they noted that they must do the things men do because if they do not then no one will do it for them.

“These roles have not changed because respect and submission a woman gives to a man is the same. It will not change.” (Interview with participant 3, February 2012).

“Roles have changed. When people were home, they lived differently but now the war changed the attitudes of people making them act in another way. It has empowered women. In the past, women would leave the heavy work and money issues to the men but now you see women, married and without husbands, have become more active in heavy work and savings.” (Interview with participant 28, March 2012).

“What do we think since women can now climb roofs, we are the same as men? I put on trousers. We climb just because there are no men. If there was a man we wouldn’t climb. We climb because of problems. So now, we are doing things done by men, but we are not doing it out of our own will, we are doing it because we have no option.” (FGD 1: participant 1, March 2012).

4.3 Measuring Success

Understanding how these women measure their successes and failures and the mechanisms which they utilize in order to achieve their goals ultimately reveals shifts in their perceptions and capabilities. As was revealed in the FGDs, the women in question have specific functionings which they themselves view as important to them and they strive to achieve these functionings and ultimately their subjective well-being. Their participation in activities such as farming, selling in markets, aleya and savings groups culminates in their ability to transform these activities into successful livelihood endeavours and ultimately use the fruits of their labour towards activities they perceive as worthy and relevant.

The concept of the strength of the homestead was frequently cited as the ultimate reason why specific livelihood activities are pursued. However, the strength of the homestead is far more complex than this physical description reveals. These women considered the strength of their homesteads to be dependent upon two factors: the ability of their children to receive as much education as possible, both in the general sense of formal schooling and in learning traditional practices and culture; as well as the physical stability of the homestead which includes both infrastructure, successes in livelihood pursuits and familial ‘intactness’.

“If a woman dies and leaves the man with kids, the man is going to disperse the kids. He disperses them because he does not have the ability to take care of them. But if it is a woman’s husband who has died, the woman will take care of the kids. When it comes to education, even though it isn’t easy, we struggle to send these children to school because it is important.” (FGD 2: participant 3, March 2012).

The number of women who felt their homesteads were strong, despite acknowledging their poverty, exuded a confidence which they further expounded upon by explaining that despite knowing they could remarry if they wanted to, they choose not to because they see the presence of a male figure as a danger to the stability of their homestead. From their perspective, the war has damaged men badly and created a perpetual cycle of alcoholism, truancy and abuse; they specifically make a choice not to enter into a marriage because they do not want their children, especially their sons, to grow up and assume that the mannerisms of men affected by the war is how a proper man should act.

“Men today are not honest anymore; you go to a man’s house nowadays and you find his children rebellious; you must force them to go to school. The life in the house is really bad and you find that people like widows are living in much better conditions than the women who are married. We manage our households very well and the children are living a good life.” (FGD 2: participant 1, March 2012).

“Men are men. We have not refused that men are physically strong and have energy. But if you go to a home that is run by men, you will come back disappointed. In case a child having to abstain from school because of no school fees, then you tell this to a man, the man gets so angry. He will tell you there is absolutely no money … then later he will get up and go to the trading centre only to come home very drunk. Married women are facing as many problems as widows. At least for a widow, she knows she has no husband so she must do everything on her own … she will struggle, but she will also manage. Women with husbands are suffering much more, because the man cannot take care of the home. Widows do everything and they spend all their energy to see that their homes and their children are really fine. Earlier it was different. Our men used to work hard, they used to take care of the homes … but now it is different.” (FGD 2: participant 4, March 2012).

This conscientious choice of remaining without a husband is significant because it signifies the capability to make a decision either employ or ignore a cultural construct at the peril of personal and social consequence; however, this choice only exists if they have access to land. From their point of view, as far as an economic standpoint is concerned, the need for a husband is irrelevant because they are not only confident enough to pursue their livelihoods, albeit with the help and encouragement of other women sharing their situation, they are also physically capable and have physical evidence of their successes.

4.4 Social Consequences of Renegotiation

Each of the previous questions has answers which will challenge notions of culture within the Acholi. Women being able to hold on to their autonomy and be responsible for their own actions and their ability to create a stable homestead for themselves and their children is noteworthy in a society where being part of a marriage is supposed to generate this stability, which is not possible without access to land. As noted before, the notion that renegotiation is taking place, in the strictest sense of the word, is debatable; rather, the increase in responsibility is an exercise in female agency and has the capability to challenge notions of culture within the Acholi. The education and examples they provide for their children, in their eyes, will impact the way their children approach things such as notions of stratified gender roles and marriage. The personal choice of the majority of the women interviewed not to remarry, despite the opportunity, is at odds with cultural constructs in the area and is significant in terms of capabilities because this particular capability they conscientiously choose not to utilize has an impact on their ability to secure a livelihood as well as their station within Acholi culture.

“We women have given up looking for men and have decided that instead of getting a man, let us struggle and go it alone. We are also in a women’s group and when you hear that one of us has a problem, you go to her and you encourage her. All of us have decided that we cannot stay with men anymore and as we all decided that if this is the way that it is, then I can live on my own.” (FGD 1: participant 3, March 2013).

Quite possibly the most apparent action these women take which will have implications on the future is the roles they pass on to their children. As explained during the FGDs, passing traditional knowledge to their children, some of which for some time were only exposed to life in the camps, is of the utmost importance. However, equally important to these women is the notion of equipping their children with modern knowledge, especially regarding gender roles, because they see the exchange of these roles as a variable that counters inequality between men and women. Teaching both boy and girl children both sets of roles fosters a sense of independence from their perspectives; in doing so, they feel they adequately prepare their children for whatever the future holds for them. It is in this light and in undertaking the responsibility to break the cycle of male disenfranchisement that they teach their children in this manner. While the accomplishments of these widows are formidable, their legacy will manifest in the actions and subjective well-beings of their children.

“I grew up in the traditional way and now that things have changed, I want to teach my children the way my parents taught me. I will never allow my children (boys) to grow up and be like their fathers because if they do that, they will perpetuate the cycle. I feel that I should train a child to do everything … not just what a man or a woman does … regardless of its sex. Also, if it is a boy and he grows up and he brings a wife, I want to make sure they do everything together. There should be no difference in roles according to a man or a woman.” (FGD 2: participant 1, March 2012).

“Our children should be taught according to the old traditions. They should not grow up looking at the men around them and think that that is the way that things should be done. They should learn to respect tradition. But for the girls, we are teaching them to do different things because you never know what the future holds for them. She might end up with a bad man, but if she knows how to take care of herself (light and heavy farming), she will not be in any trouble.” (FGD 2: participant 2, March 2013).

As Acholi culture is predominately patriarchal, where women are not afforded as much social latitude as men with respect to domestic and social lives as well as land access and livelihood accomplishments, educating children in both tradition and in modern changes could potentially cause a more significant and permanent renegotiation in the future.

The choice to remarry and whether or not this decision would be in their best interests is a quandary that has not escaped these women’s attention. In the FGDs, they reiterated time and time again how they felt about men; sentiments such as “men are not honest”, “men are not useful anymore”, “women with husbands are suffering much more”, “men drink too much, steal from their families and abuse their families”, “inviting a man into your home puts you at risk for disease” and “men used to work hard and take care of their families, but now things are different”, were pervasive throughout the discussions. Possibly the most poignant assertions were directed at the fact that the actions of men in the community have changed in the time since the war began, ended and return was made possible. These women are fully aware that the conflict has had a significant impact on men and that the disenfranchisement they experienced during the war and internment has followed them home.

“Living in the camps spoiled and disorganized everything. If the men hadn’t lived in the camps, they wouldn’t be doing the bad things they do now … like drinking. Before, men used to take care of their homes much better than they do today.” (FGD 2: participant 9, March 2012).

That being said, cultural constructs which dictate marriage, land access and overall stature within the community are also being taken into account when they make their decision. “Marriage is traditionally one of the most important social customs in Uganda … .marriage confers on both men and women a high social status … because Uganda is a patriarchal society, women do not inherit property, especially land (except in Buganda). Thus women have traditionally been expected to marry, even to polygamous men, if only to secure land and livestock, which are important sources of livelihood in Uganda’s agrarian society” (Otiso 2006: 82). For the Acholi people, these characteristics hold true and therefore construct a difficult situation for these widows. They have the capability to remarry, which would satisfy cultural requisites but expose them to the scenarios and characteristics they described in the FGD or they choose to not to exercise their capability to remarry which, despite being culturally abrasive, keeps their other capabilities and functionings intact.

The education provided to their children concerning the roles of men and women with special consideration given to ensuring that the cycle of disenfranchisement does not continue to future generations as well as the conscientious choice not to exercise the capability of remarrying both have important implications for future generations. One action seeks to re-establish cultural norms with the addition of attempting to equalize the roles of men and women to make them more prepared for an uncertain future; the other action is initiated to protect the subjective well-being of the family at this juncture in time. However, as time passes and the education of children begins to manifest in action, there exist the potential for attitudes towards gender roles and marriage to shift with a profound impact on cultural norms.

5. Conclusion

The case study sought to establish how a vulnerable demographic such as widows, in the face of cultural and societal constrictions regarding land access and security convoluted by conflict, is able to utilize the resources they can access and generate livelihoods they deem relevant. The return process has not been easy as, despite the relative peace which has returned to the area, conflict still abounds within villages and clans where land rights and cultural attitudes are a matter of concern. While significant renegotiation with regard to gender roles, in the strictest sense of the word, hasn’t taken place with any distinct significance, there has been a distinct change in the actions of these women and how they perceive their actions; their activities would more appropriately be described as an increase in responsibility and increase in workload. However, this is just as important as a renegotiation where livelihood access is concerned. There is a connection between the activities these women claim responsibility for, their successes while engaged in these activities, and how they apply the results towards the future. Instead of exercising the capability of remarrying and securing tenure and livelihoods in this manner, as long as they have access to land and feel confident the customary tenure system will provide for them, they conscientiously choose widowhood over marriage because they feel their activities are successful and don’t warrant the need of a husband. They also acknowledge the fractures within their own culture which the conflict caused and are actively pursuing solutions through the way they educate their children and their unwillingness to expose their families to a potentially abusive, truant, diseased and alcohol dependent male figure. However, despite these notions, access to land is paramount as it is the only resource which can encourage agency and growth. In this respect, within the small confines of the study area, these women are leading agents of change in the sense that their activities are progressive and their desires lie in a return of culture and stability; their capabilities and willingness to engage in actions which will ensure cultural shifts and changes is palpable.

References

Adoko, J; Levine, S. (2004). Land Matters in Displacement: The Importance of Land Rights in Acholiland and what Threatens Them. CSOPNU – Civil Society Organisations for Peace in Northern Uganda.

Adoko, J et al. (2011). ‘Understanding and Strengthening Women’s Land Rights Under Customary Tenure in Uganda,’ in Land and Equity Movement in Uganda (LEMU). Discussion Paper. Accessed at http://landportal.info/resource/research-paper/womens-land-rights-and-customary-tenure-uganda.

Afshar, Haleh & Eade, Deborah (2004). Development, Women, and War: Feminist Perspectives. Oxford: Oxfam.

Benjamin, Judy A. & Fancy, Khadija (1998). The Gendered Dimensions of Internal Displacement: Concept Paper and Annotated Bibliography. UNICEF, Office of Emergency Programs.

Berhane-Selassie, Tsehai (2009). ‘The Gendered Economy of the Return Migration of Internally Displaced Women in Sierra Leone.’ European Journal of Development Research 21 (2009): 737-51.

Bernard, H. Russell (1994). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Campbell, Patricia J. (2005). ‘Gender and Post-Conflict Civil Society: Eritrea’. International Feminist Journal of Politics. September 2005. Vol. 7, No. 3: 377-399.

Carpenter, Charlie R. (2005). ‘Women, Children and Other Vulnerable Groups: Gender, Strategic Frames and the Protection of Civilians as a Transnational Issue.’ International Studies Quarterly 49.2 (2005): 295-334.

DeMunck, Victor C. (2009). Research Design and Methods for Studying Cultures. Lanham, MD: Altamira.

Dolan, Chris (2009). Social Torture: the Case of Northern Uganda, 1986-2006. New York: Berghahn.

Doss, Cheryl et al. (2012). ‘Women, Marriage and Asset Inheritance in Uganda.’ Development Policy Review. 30.5: 597-616.

Finnström, Sverker (2003). Living with Bad Surroundings: War and Existential Uncertainty in Acholiland, Northern Uganda. Uppsala: Dept. of Cultural Anthropology, Uppsala University.

GoU – Government of Uganda/ District Camp Phase-out Committee (2010). District Camp Phase-out Committee Joint Camp Assessment Report February 24th-26th and March 9th– 12th 2010. www.internal-displacement.org, retrieved 29 August 2012.

GoU – Government of Uganda/ Ministry of Health (2005). Health and Mortality Survey among Internally Displaced Persons in Gulu, Kitgum and Pader Districts, Northern Uganda. Geneva: World Health Organization.

GoU – Government of Uganda/ Office of the Prime Minister (n.d.). Camp Phase-out Guidelines for all Districts that have IDP Camps. Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. www.internal-displacement.org, retrieved 29 August 2012.

GoU – Government of Uganda/ PRDP (2006). Peace, Recovery and Development Plan for Northern Uganda. Kampala: GoU document.

Klein, Renate & Wallner, Bernard (2004). Conflict, Gender, and Violence. Innsbruck: StudienVerlag,

Meintjes, S., Pillay, A. & Turshen, M. (2001). ‘There is no aftermath for Women.’ In: The Aftermath: Women in Post-Conflict Transformation, ed. by Meintjes, Shiela; Pillay, Anu & Durshen, Meredeth. Zed Books. London: 3-18.

Moser, Caroline O. N. & Clark, Fiona C. (2001). Victims, Perpetrators or Actors? Gender, Armed Conflict and Political Violence. London: Zed.

Nussbaum, Martha Craven & Jonathan Glover (1995). Women, Culture, and Development: A Study of Human Capabilities. Oxford: Clarendon.

Nussbaum, Martha (1999). ‘Women and Equality: The Capabilities Approach.’ International Labour Review 138.3 (1999): 227-45.

Nussbaum, Martha Craven (2000). Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Otiso, Kefa M. (2006) Culture and Customs of Uganda. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Potash, Betty (1986). Widows in African Societies: Choices and Constraints. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Sen, Amartya (1999). Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, Amartya (1992). Inequality Re-examined. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Sen, Amartya (1984). Resources, Values, and Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sweetman, Caroline (2005). Gender, Peacebuilding, and Reconstruction. Oxford: Oxfam.

Tripp, Aili Mari (2004). ‘Women’s Movements, Customary Law, and Land Rights in Africa: The Case of Uganda.’ African Studies Quarterly, Vol 7, Issue 4, Spring 2004.

Turshen, Meredeth (2002). The Aftermath: Women in Post Conflict Transformation. London: Zed Books.

Maps:

UCC – Uganda Communications Commission (2010). Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF). RCDF Projects in Gulu District, Uganda. www.ucc.co.ug/files/downloads/GULU.pdf, retrieved 15 March 2012.

CIA World Factbook (2012). Central Intelligence Agency CIA World Factbook: Uganda. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ug.html, retrieved 15 March 2012.

UNHCR – United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2007). Uganda: Patiko Subcounty (as of November 2007). Map. UN High Commission for Refugees, 30 Nov. 2007. Reliefweb.int. http://reliefweb.int/map/uganda/uganda-patiko-subcounty-november-2077, retrieved 15 March 2012.

[1] This paper is based on the forthcoming publication: Göttsches, Megan (2014): Livelihood Access and Gender Role Renegotiation. A Case Study of Widows in Northern Uganda. Culture and Environment in Africa Series, Issue 4: The University of Cologne, MA Culture and Environment in Africa Programme.

[2] ‘assumed’ is used here because this study did look at these women’s specific situation; however, this would be an important focus of research with regard to land tenure and marriage systems in the conflict and post-conflict settings.

[3] The term ‘complex tenure’ is a coinage of the author for reference to convoluted processes of land access; this involves land access that does not include customary tenure, leasing land, returning to natal lands, or any other type of traditionally appropriate method of access.

[4] It is important before proceeding to distinguish between access, ownership and user rights; the scope of this paper is dedicated to simple land access as the research had neither the capacity nor time to explore the existence and connections between these three characteristics which can be applied to land. However, this relationship is worthy of further scrutiny.

[5] Though obtaining data from all over the district may have provided a broad overview for the research, within the given time frame for gathering empirical data, this would not have been feasible.

[6] Patalira is located some distance from the trading centre at Patiko-Ajulu. Thus it was decided, due to time constraints, that it be unengaged by the research.

[7] The thirty participants of the target population participated in the free-listing exercises. Each participant was asked to generate an exhaustive list of key terms which came to mind when asked the questions “what did men/women do before/during/after the war and now?” This question was repeated for each gender category over the four defined time periods. Concerning livelihoods, the question of “what types of work do YOU do?” was posed. Again, this question was posed over the four defined time periods. Each participant created nine free-lists, which equated to over 3,000 pieces of data during the analysis period. Section 4.2 presents this data in its most distilled form through the use of visually weighted lists as opposed to tables and numbers.

[8] Time constraints, road conditions and weather limited the number of questionnaires for the quantitative survey that could be administered. The target was set for a minimum of 100 questionnaires.

[9] The Luo term for ‘group farming’ or ‘working together’. There are many forms of aleya and in the past, where farming was concerned, it was often done just with men. However, women (both married and widowed) have come together to create aleya groups of between 10-30 people which operate on a sub-village level and rotate days spending time on the farms of members. Its foundation is rooted in a shared labour philosophy which benefits all involved.

[10] Each graphic prominently displays actions which were repeated in each category; larger actions denote higher repetition as smaller actions exemplify lower repetition – compiled from free-listing data by the author after the fieldwork period.