Sam Dubal

Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, USA

Abstract

The forced conscription of soldiers and forced marriages within rebel ranks are among the crimes against humanity that the International Criminal Court (ICC) and others have charged against the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). Based on thirteen months of ethnographic fieldwork with former LRA rebels, this article examines rebel kinship, or the forms of meaningful social life that were formed through forced conscription and forced marriage. Focusing on a forced marriage between two rebels and a sense of militant kinship fostered within the LRA, I show how rebels live and lived beyond the moral boundaries of the static social-philosophical construct known as ‘humanity’. I argue that reading violence and its consequences through the moral paradigm of humanity – in which violence necessarily dissolves rather than forges social life – precludes a genuine understanding of profound forms of life that emerge in its aftermath.

In the eyes of most of the humanitarian West – including the International Criminal Court (ICC) – many LRA practices constituted crimes against humanity. Among the charges of crimes against humanity that the ICC levelled at LRA commanders are forced conscription of soldiers and forced marriages within the rebel ranks. Characterised as absolutely inhuman, these acts are thought to constitute a seriously violent evil beyond the pale of humanity.

Although many of these acts were indeed violent, this did not imply that meaningful and valued relationships did not form in the aftermath of these so-called crimes. Simply understanding (and dismissing) these crimes as ‘against humanity’ fails to appreciate the dynamic breadth of rebel kinship that flourished in and through the violence of the war – forms of meaningful and often non-violent social life that were lived beyond the moral limits prescribed by the social-philosophical construct known as ‘humanity’. This article explores the forms of social connection forged rather than dissolved through violence, shifting who related to each other and how in unexpected ways. In doing so, it attempts to open new moral spaces beyond the boundaries of the good that the amorphous concept of ‘humanity’ delimits.

It begins with the story of Amito, a woman forcibly abducted and married into the LRA who unpredictably develops close ties to her husband and his family, creating love out of violence. It then examines the forms of militant kinship that formed out of forced conscription, a kinship that sometimes coalesced into a sense that the LRA had itself become a clan.

The material upon which this work draws stems primarily from thirteen uninterrupted months of ethnographic research undertaken in and around Acholiland in northern Uganda, from July 2012 to August 2013, following a shorter spell of research from June to August 2009. I spent most of this time learning from networks of former LRA rebels through a variety of research methods, including participant observation and semi-structured interviews. These networks included men and women who had spent varying amounts of time as or with the rebels, ranging from a few days to over two decades, and with varying ranks, ranging from no rank up to high-ranking commanders. Taken together as a group, these rebels had participated in almost all phases of the war, from the beginning and up until the present. Rather than refer to them as ‘respondents’ or ‘informants’ or ‘interlocutors’ throughout this piece, I name them as ‘friends’, because this more accurately describes how I see them. All names appearing here are pseudonyms.

Violent Love: The Problem of Inheriting Amito

‘Who shall fight for love?’

A pregnant woman, cradling her distended tummy, asks her unborn baby, in a line from Acholi playwright Judith Adong’s production ‘Silent Voices’ (performed at the National Theatre, Kampala, in July 2012). The play reproduced a humanitarian narrative about civilians caught between the violence of the UPDF and the LRA. It ended with a song imploring the audience: ‘Don’t let innocence die!’; ‘Save love, save the future!’

As she told me, Amito was forcefully abducted by the LRA from her village home in northern Acholiland in the late 1990s, near the border with what is now South Sudan. She was about 11 or 12 years old. She became a babysitter (ting ting) for Onen, an LRA officer who was keeping five wives, the most senior of whom was Gunya. At first, Amito looked after Gunya’s children. Within a short time, she became Onen’s sixth wife. She gave birth to Ojara, her first child with Onen, at the age of fourteen. She wanted to escape and did not want to stay with Onen, who took her as his wife by force.

When Amito first narrated this story to me, she was emotional and tearful. Her narrative followed the arc of the story often told about women in the LRA, according to which young girls were kidnapped and made sexual slaves of male rebels. By legal definition, she was abducted, defiled, and raped – entering a ‘forced marriage.’ As two human rights scholars of marriages between LRA men and women adamantly declare, ‘Forced marriage as it was practiced by the LRA is a crime against humanity’ (Carlson & Mazurana 2008: 64). Even scholarly accounts that attempt to disrupt this narrative by questioning the image of the passive female victim of war or by contextualising abduction of women within Acholi marriage customs emphasise that such marriages were forced, always referring to women in these arrangements as ‘wives,’ in ersatz quotes (see e.g. McKay & Mazurana 2004, Allen & Schomerus 2006, and Annan et al. 2009; Baines 2014 is a rare exception in dropping, as I do, ersatz quotes).

These morally charged labels offer very little understanding of the complexity of what followed in Amito’s experience as Onen’s wife (a term that in her case cannot justifiably be qualified with ersatz quotes). As she continued her story, she began to remember her co-wives – who they were, where they came from, and what their relationships were like with each other and with Onen. Amito’s facial expressions and storyline changed dramatically. She was Onen’s most beloved wife. Everyone told her that Onen loved her the most. Her co-wives (nyeggi) became filled with jealousy (nyeko) of her, performing a language in which the word used to signify ‘jealousy’ is also used to signify ‘co-wife.’ Amito worried that they were plotting to kill her while Onen was away, planning to throw her body into the bush (lum) and to blame her death on the Lotuko people, a tribe in South Sudan. Amito told Onen about these plans, and he began to protect her from his other co-wives. He also called together his co-wives and asked them to explain what had happened, warning them that jealousy was illegal among LRA co-wives. Indeed, many of my friends reflected that jealousy was well-regulated and that co-wives lived together more harmoniously as rebels in the LRA than as civilians. Fights between jealous co-wives in the lum were dangerous because they could bring injury or death to the husband in battle. Onen’s own finger was injured because of a fight between Gunya and another of her co-wives.

Once, she recalled wistfully, she suffered a bad injury. Government troops had tossed bombs at the rebels, and one of them landed near her, felling her on the battlefield and rendering her unable to move due to the severity of her wounds. The rebels ran away, and she was abandoned. But Onen had not forgotten her. He searched for her for three days before finding her and carrying her back to the LRA defence, where he put warm water on her wounds. He struggled for a month to procure medicine for her and cared for her wounds until they healed. Amito saw others killed or dying in the lum, but found that Onen took excellent care of her. After she delivered Ojara, she saw Onen’s love for her grow. He sought to find a way to return Ojara to Amito’s mother, Min Amito, to keep him safe.

On closer inspection, the relationship that developed between Amito and Onen was hardly the ‘crime against humanity’ that its inception is often characterised to be. He was, as the quote opening this section asks, precisely the one fighting for love. Yet just as his forced marriage to Amito was seen as a ‘crime against humanity,’ his love for Amito was considered incompatible with and antithetical to the violence he committed as a rebel.

After about six years with Onen, Amito left the LRA. She was separated in the course of a battle and captured by the UPDF before being sent to the World Vision reception centre. Though she was happy with Onen, she found life in the lum hard and was secretly longing to leave the frontlines. She did not know how to ask Onen to send her home, though, as he wanted her to stay with him there. While staying at the reception centre, she was delighted to reunite with her mother. She was bitter and angry to learn, however, that while she was with the LRA, the rebels had killed her father, ambushing a vehicle he was travelling in and shooting him dead.

Members of Onen’s family also came to see her in the reception centre – an act of social recognition that might be unexpected for a ‘crime against humanity.’ Hearing that one of Onen’s wives had returned, Mohammed, Onen’s first cousin and a former LRA military policeman, was there. So too were two of Onen’s brothers. When Amito finished her required time at the centre and prepared to leave, Mohammed helped her carry her things to her mother’s place in town.

At first, she decided to spend some time with her mother. She was unsure of what the future held for her and Onen, but she planned to wait for him to return too, without a desire to get another man. She noticed that so many of her friends she had left behind when she went to the lum had died of HIV/AIDS, and she was grateful that she had been abducted so as to have escaped their fate. In time, people around her began to ask why she was waiting for this man who was still in the lum. They questioned how long she would wait for him to come back. Some advised her to continue to wait for him. Others, including staff at the World Vision reception centre, advised her to forget him. In fact, they insisted that Onen had abducted her forcefully and told her that she should pray that he would die. Amito told me that she found this ‘rather stupid talk’ (lok ming ming). Her mother Min Amito called this ‘really bad’ (rac tutwal). Instead, Amito prayed daily that he – the father of her son, the husband who took care of her and someone whom she could not let go of – would come home safely. Onen was also abducted against his will, she retorted to the staff. She angrily asked them if praying for someone’s death was consistent with the evangelical teachings of World Vision. Though others found her relationship with Onen morally unacceptable given the violence in which it was forged, Amito deeply valued it and longed for him.

Kinship in Question: The Conflict over Inheriting Amito

Soon enough, Amito decided she wanted to go visit Onen’s family in their rural home in Palik (a pseudonym). So she, Min Amito, and Ojara journeyed from town to visit them. They were happy to see her and welcomed her and their son, Ojara, who bore a striking resemblance to his father. Amito wanted to stay with them there, and so did Onen’s family. They respected her and told her that if Onen were to come back, they would be married. This would be her home, and there would be land for Ojara to dig on, they assured her. Though entitled to ask for a fine for keeping Ojara (latin luk), Min Amito and Amito had not yet done so, a claim respectfully reserved. This was hardly a typical relationship between the family of someone who was ‘raped’ and ‘forcibly married’ and the family of the ‘rapist.’

Amito wanted to stay in Palik, but she wondered who would take care of her there as she waited for Onen. She did not have to wait long to find an answer. She soon perceived that Mohammed was indirectly courting her, starting by being very supportive of her and Ojara. Mohammed bought Ojara clothes, books, and shoes, and began paying for his school fees. Mohammed and Amito had only known each other as acquaintances in the lum. Onen had introduced Mohammed to Amito as his cousin-brother, the son of his father’s brother. But Amito and Mohammed were in different battalions and did not get to know each other well until they both returned from the frontlines. Mohammed, Amito recalls, started courting her from afar, like a cat trying to get food sitting on a table, sneaking steadily closer and closer. He was a bit shy and fearful, and not at all direct in his courtship, she remembered.

Once, he took Amito on a motorcycle taxi (boda boda) from town to Palik to harvest some crops. On that trip, Amito witnessed a growing conflict between Onen’s family and Mohammed’s family. She wanted to stay in Palik with Mohammed’s family, but Onen’s family was furious about this. Sensing that an intra-clan dispute was about to erupt with her at the centre, Amito broke off her nascent relationship with Mohammed. At the heart of this conflict between the families was a contestation over kinship, wealth, and social death manifesting in a dispute over widow inheritance. By conventional kinship rules, Mohammed had little right to inherit Amito. It was only through the militant kinship that he had forged with Onen in the lum that he staked his claim against those of Onen’s brothers.

Widow Inheritance in Acholiland

Widow inheritance (lako dako) was until more recently a common feature of customary Acholi social life. As a respected elder, Ogweno Lakor, and others described it, lako occurred when a woman’s husband died and the late husband’s brother took over as the woman’s new husband. The woman was allowed to choose which of the brothers she wanted to marry, with whom she would begin staying following a cleansing ceremony involving the ritual use of a chicken (buku gweno). The chosen brother could not refuse to take care of her and her children. Often, the chosen brother was close to her family and helpful to them while her husband was still alive. A brother produced from the same mother was considered most eligible, though brothers from the same father but different mothers were also considered. Cousin brothers (sons of brothers) or clan brothers (men of the same clan) could be chosen, Ogweno Lakor said, on the condition that there was precedence in the family for such a practice. If there was not, the clan brother would be treated as an outsider and obligated to marry the woman with cash, paid not to the widow’s family, but to the deceased husband’s family. By contrast, inheritance by brothers from the same mother or father paid nothing, assuming the wife had been formally married to her first husband. Inheritance by the closest male friend of the deceased was almost unheard of; such an inheritance would also require payment to the deceased husband’s family, and would, Ogweno Lakor warned, cause great enmity between the friend and the deceased’s brothers. Given how integral the wife and her children were considered to the family, to whom they customarily belonged after marriage and part of whose wealth they constituted, the brothers might even seek to kill the friend for inheriting their wife. By taking their wife, such a man would be mocking and insulting the clan, as though it had no remaining men to care for a wife.

Conflict also arose if the process of inheriting a wife took place while the first husband was still alive. According to some, including Ogweno Lakor, inheriting the wife of a man still alive but perhaps working abroad or living far away was a serious offense. The only way for a husband’s brother to help the wife in this situation, he insisted, was to keep the children, dig her garden, buy clothes for them, and the like – but by no means should the brother have sexual intercourse with the wife, as it was presumed that the husband would someday return. There were, however, situations in which a husband was presumed to have died when in fact he had not. In these cases – not uncommon during World War II and the LRA war – a soldier or rebel returning home might find that his wife had been inherited by his brother, with whom she may have produced more clan-children. In this case, elders returned the wife to the original husband after a cleansing ceremony, and the brother was told to never go back to the inherited wife ever again. If he did not heed this advice, conflict would arise between him and his brother, the original husband.

Mohammed’s Attempt to Inherit Amito

Mohammed’s suspected attempt to inherit Amito was contested precisely over many of these customs. As Amito and Min Amito saw it, Onen’s immediate brothers wanted to inherit Amito, and together with their mother Min Onen, were unhappy that Mohammed – a cousin brother – was trying to court her. Min Amito told me that she heard rumours that Min Onen had tried to curse Mohammed for attempting to inherit Amito.

At first, Min Onen denied these rumours to me. She claimed that she would be happy if Mohammed inherited Amito. She lamented that her own sons (Onen’s brothers) were not responsible enough to take care of Amito, nor were they capable of dealing with the jealousy (nyeko) that their own wives would have towards Amito if she were to become a co-wife to them. Min Onen, together with her son Obwola (Onen’s brother), suggested that Mohammed was helping Amito and Ojara because of how caring Onen was to him in the lum. Onen helped to facilitate Mohammed’s return from the frontlines, after all, she recalled. But later, she adamantly proclaimed that her own sons should be the ones to inherit Amito. Only if all her sons had died, she insisted, would the more distantly-related cousin-brother Mohammed be allowed to inherit Amito. A prominent chief of the official organisation of Acholi chiefdoms, Ker Kwaro Acholi, confirmed Min Onen’s assessment when I presented this case to him in hypothetical, anonymized terms – the brothers, not the cousin-brother (Mohammed), should inherit the wife.

On the surface, it appeared that customary kinship rules clearly excluded Mohammed from inheriting Amito ahead of Onen’s brothers. But these rules were fundamentally challenged by new forms of rebel kinship, particularly brotherhood, developed in the lum with the LRA and under conditions of intense violence. Gunya, for whom – together with her and Onen’s child – Mohammed also cared, told me that she agreed that Onen and Mohammed were not immediate brothers, but said that they were close friends who were like brothers. She argued that because they had stayed closely together in the lum, and Mohammed had cared for Onen’s wives there as though he were Onen’s real brother, he himself is the true brother (omin Onen ki kome). She remembered that like a true brother, he welcomed Onen’s new wives into their home in the lum, joking, talking, and playing with them as they adjusted to their new family. He helped develop Gunya and Onen’s relationship, facilitating their courtship and earning her respect as a responsible brother to Onen. He took better care of Onen’s children than Onen’s biological brothers did, she reflected to me. She suggested that if Onen were to come out of the lum, he would be angered by the way in which his brothers had neglected his wives and children. Both because of the time he spent with Onen in the lum and the way in which he took responsibility for Onen’s wives and children, Mohammed had effectively confronted existing rules of kinship and staked his claim as more than a mere cousin-brother to Onen – and therefore the first-choice to inherit Amito, as illustrated in the figure below.

Family genealogy with focus on relationships of Onen, Mohammed, and Amito (all outlined in red). Note the transgressive relationships between Onen and Mohammed as ‘true’ brothers (marked by green railroad track) and between Mohammed and Amito as potential husband and wife (marked by circle on green line). Figures marked with ‘x’ are deceased. Onen is marked with a slash, representing the precarity of his social life living in the lum.

Mohammed told me that he felt similarly, feeling that he had a special bond with and special directions from Onen, based on their time together in the LRA. Before Amito had become Onen’s wife, Mohammed narrated, Onen had suggested to him that he court Amito. Mohammed refused, saying he did not want to keep a wife in the lum because of the control the LRA asserted over married couples (see also Dolan 2009: 296; Baines 2014). But he and Onen grew close fighting together in the lum. Their brotherhood remained strong and was melodically commemorated in the form of Mohammed’s ringtone. Whenever his phone rang, it blasted out the sound of a sequence of rapid machine gunfire. He explained how he chose his ringtone:

There was a time when [Onen and I] came for operations here [in Uganda]. When we reached a field which was well-cleared, a gunship reached and found us there on the bare field. I was with Onen and he was shouting, ‘This gunship is going to kill me and my brother today. God help us.’ The gunship came and started firing at us. We all went down but Onen still got up and ran to check whether I was alive. So, when [the phone rings] I start thinking about how the gunship came and shot at us but we didn’t die, and again remember how Onen and I used to make fun of this, because we would laugh at each other about how we panicked and the way he was shouting. So, [the ringtone is] for remembering what happened to us.

Yet while he may have made a new claim of rebel brotherhood to Onen, Mohammed also posed a threat to Onen’s existence with his suspected courtship of Amito. As Min Amito stressed, Onen was still alive in the lum, and so any talk of lako was premature. Indeed, Onen’s family received updates every now and again about his status, often from those rebels recently returned from the frontlines. Min Onen insisted to me that inheriting a wife whose husband was still alive would curse the husband to an untimely death, inflicted wherever he was. This is why, she suggested, some women were particularly keen to avoid having sex with other men while their husbands were away at e.g. war – it was thought that such illicit sex (lukiro) would lead to the husband’s death. Mohammed’s courting of Amito touched on the difficult subject of Onen’s very life. There was an enduring uncertainty as to whether he would ever return alive from the lum, having spent over two decades with the LRA. The question of who would inherit Amito had not only begun to push Onen into a zone of social death, but physically threatened his very life. Onen’s family suggested that Mohammed, in surreptitiously aiding Amito so that he could inherit her when Onen died, was wishing death upon Onen.

As a relatively successful man making money in town, Mohammed also attracted the jealousy of his cousin-brothers with his pursuit of Amito. While some of Onen’s brothers also worked in town, they had their own families to care for and were struggling for money. Mohammed was seen to be both unattached and comparatively richer, in addition to being among the more responsible men in his clan.

Mohammed was not the only one imagined to have wealth and status in this situation. Were Onen to come back from the lum, Gunya pointed out, he would become a moneyed big man, most likely converted to work for the government or UPDF in some capacity. (Of course, were the LRA to win the war, his status would be even higher). Gunya suggested that were Onen to return to see how poorly his immediate brothers had treated his wives and children, he would angrily refuse them patronage.

Mohammed himself acknowledged that Onen’s family began to suspect him of trying to inherit Amito. He continually denied these claims, insisting that he only helped Amito and Ojara because no one else was doing so. He also agreed that no one should inherit Amito as long as Onen was still alive. Indeed, he recalled that he and Onen lived well together in the lum, and he believed that Onen wanted him to continue to help Amito while Onen remained in the lum. He felt that Onen’s immediate family was unable to help Amito, and that they erroneously thought that this meant that he should not help her either. But, having incurred their wrath, he began to pull back and became more reserved when it came to helping Amito, Gunya, and another of Onen’s wives who had returned from the lum.

Before Mohammed had returned from the frontlines, he recalled, Onen instructed him that his clan should take care of his children who had returned from the LRA, even if he died. Mohammed refused to renege on the responsibility he felt Onen had given him. After Mohammed returned from the LRA, and from time-to-time, he and Onen communicated on the phone. When Amito returned home, Onen called Mohammed and asked him to go see her. He wanted Mohammed to let his other wives know that he did not expect them to wait for him to return, that they should feel free to find other men if they liked. But he had different plans with Amito, whom he promised he would marry when he returned. Indeed, Mohammed recalled, when Onen occasionally called into the radio show Dwog Cen Paco, he always greeted Amito first, sometimes even asking the host Lacambel to go to Amito and Min Amito’s home so that he could directly talk to them – but not Gunya nor his other wife.

Amito’s Nostalgia for Onen Grows

As Mohammed remembered, when Amito came back from the lum, she often sought him out for life advice, including wisdom on what she should do about her husband. Mohammed told Amito that she was free to find another man if she wanted. But he told her that once she got another man, he would inform the new husband that this woman [Amito] with whom he would be staying was ‘our wife’ (dako-wa), and that when her husband [Onen] returned, he might take her away.

Both Amito and Min Amito knew of Onen’s plans to marry Amito. So when Amito got another man in town, Anywar, Min Amito was both shocked and unhappy. As she remembered, she called Mohammed to let him know what was going on and to share her displeasure. She did not like Anywar. He did not respect her; he refused to take care of Ojara, who he made clear was not his child and therefore not his responsibility; and he was not earning money to support the family, leaving Amito to pay for both food and rent by herself. As their relationship deteriorated, Min Amito and her family grew worried about her and brought her back to Min Amito’s home together with her second child, ending their relationship.

Min Amito wanted Amito to wait for Onen. But after a year or two, she found another husband, a boda boda rider named Kidega, with whom she was staying at the time I met her. Kidega was, as far as Min Amito could tell, an equally poor husband to Amito. He too refused to have any of Amito’s other children stay with him, and so Ojara and his half-brother remained at Min Amito’s home. When Amito’s family sent Kidega a letter assessing the fine that he owed for unsanctioned elopement (luk) with their daughter, and came to see him to claim it, he did not give them a single coin – not even to help pay for transportation from their rural village to town. Min Amito felt he was very disrespectful, wanting only Amito and not her children or family. Unlike Onen’s family, his family did not seem serious about caring for Amito as their own daughter.

Min Amito had become frustrated. She never wanted Amito to take another husband in the first place. Now, Amito had been through one difficult marriage and was unhappy in her second. Moreover, Amito was pregnant again, with her third child. Min Amito wanted her daughter to wait for Onen, to come home and stay with her, or to go to Palik and stay with Onen’s family. She would have been happy if Mohammed inherited her daughter, but she too knew of the internal family conflict that prevented that from happening. Instead, she waited for Onen – a better, more mature man than either Anywar or Kidega, someone who would provide for her daughter and love her. During my last visit with her in 2013, she shared with me pictures of Onen and Amito together in the lum. She recounted a time during the war when Onen saved Amito from drowning in a strong river current, nearly drowning himself in the process. She reiterated her desire for Amito to return to Onen. Even though he took Amito as his wife without courting her, he was a responsible man, she reflected. She knew that people would stigmatise her, saying that her son-in-law was a rebel (lakwena), but she did not care. She had already given Ojara to Mohammed for him to see his father’s land, even though luk had not yet been paid – a sign of her tremendous respect for Onen.

Amito herself was torn over what to do. She told me that she wanted to accept Mohammed’s courtship and stay with him, but could not. She also wanted to wait for Onen, but was becoming more and more impatient. How long should she wait, she wondered? She knew that she wanted to produce a total of four children, but with Onen still in the lum eight years after she had returned, she had grown anxious. She also found staying alone difficult, feeling as though she needed a husband to help care for her and her family. She wanted him to come back alive, and she still dearly loved (maro) him, she said. If he returned, she would go to him, leaving behind her current husband, Kidega. Indeed, she prayed that Onen would come back so that she could be together again with him.

At the time of writing, Onen remained in the lum with the LRA, almost a decade after Amito’s return. Whether Onen would leave the lum remained as uncertain as ever. Min Amito longed for him to return from the frontlines, inferring from her daughter that he was a good, respectful, and mature man who was and would be a much better husband than either of the two men Amito had found at home (gang). He cared for Amito and their son Ojara and loved them both very much. She was not sure what Anywar or Kidega would do if Onen were to return, but she was sure that she wanted her daughter to reunite with Onen.

Forged in violence, Amito and Onen’s relationship endured, held together by strings of love and networks of kinship stewed in rebellion, and holding strong in the face of competing civilian loves and kinships. Amito and Onen were one of many couples I found that had developed a lasting relationship out of forced conscription and marriage. There were, to be sure, many relationships that also dissolved when taken out of the lum, for a variety of reasons. Sometimes the husband failed to take responsibility for his wife and chased after other women. Other times, conflict or jealousy arose among co-wives at home that made a lasting relationship impossible.

In Amito and Onen’s case, it was through violence that they had proved their love for each other. Because of the caring way in which Onen protected Amito from violence, Amito and her mother grew nostalgic for him in his absence. It was also through the rebel brotherhood that Mohammed had staked his claim as Onen’s true brother and thus challenged existing kinship rules about Amito’s inheritance. If Amito and Onen’s marriage had indeed been a ‘crime against humanity,’ it was not a crime that Amito or either of their families cared to recognise given how it had developed over time.

Militant Kinships: Brotherhood and Sisterhood in the LRA ‘Clan’

I feel as if I’ve left my clan (kaka) and am staying far away in a foreign land (rok), not in my clan (…) I still find life hard. If I were to decide again, I would choose to stay with my clan [the LRA].

Makamoi, a former LRA fighter and collaborator, reflecting on the kinship he had within the LRA and had lost since leaving the rebels

Just as some like Amito longed for their ‘forced marriage’ partners from the lum, others who had come back from the frontlines spoke glowingly of the forms of mutual being they shared with fellow rebels with whom they had been forcibly conscripted. Musa, who had returned in the early 2010s, was particularly nostalgic about the sense of brotherhood and sisterhood that rebels cherished in the lum. ‘Since I’ve returned, there has been nothing good with people at home (…) People don’t help each other. If, for example, a fire destroys all the sorghum, even your real brothers won’t help give you food to eat,’ he lamented. By contrast, Musa and many others noted, people in the lum were united. ‘In the lum, people helped each other a lot, there was a lot of sharing – of food, sugar – it was all shared to the last bit, even if it was scarce,’ he recalled. ‘This doesn’t happen at home – people only care for their own kids (…) There’s a lot of jealousy among people, people aren’t united, and they work on their own.’ He was not afraid to air his feelings on the outside of his hut.

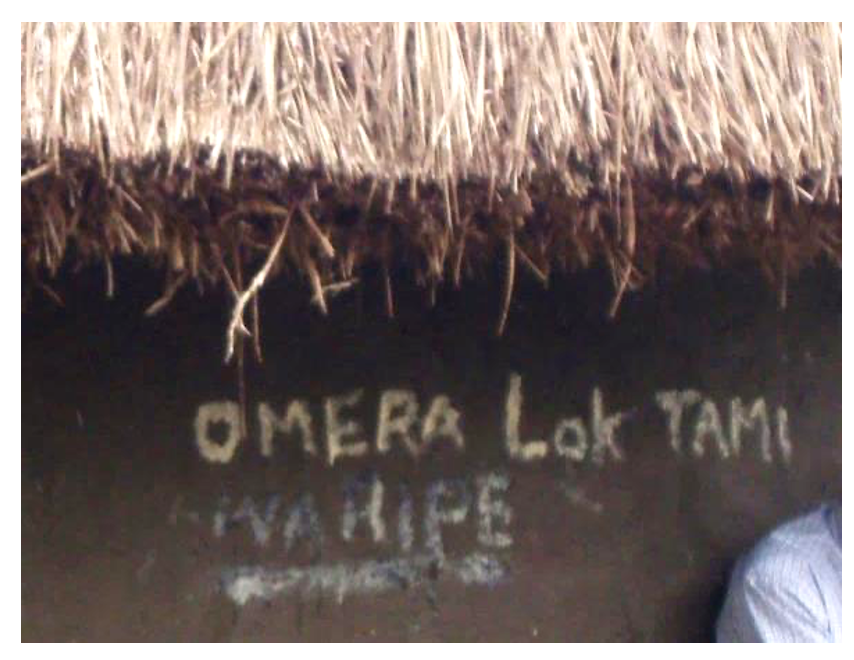

‘My brother, change your mind. Let’s unite.’ (Omera lok tami. Waripe.)

Inscription on the outside of Musa’s hut, directed toward his biological clan brothers.

He explained that in writing it, he wanted to ‘repair people’s heads’ (roco wii dano), reversing the discourse of rehabilitation centres designed to ‘reintegrate’ former LRA rebels by, as one of these organisations put it, ‘repairing’ the heads of rebels.

(Photo: Sam Dubal)

Musa articulated a sense of mutuality that is not uncommon within military groups (see e.g. Thiranagama 2011, from which the title, ‘militant kinship’, of this section is drawn). He spoke of his fellow rebels as his real brothers and sisters:

The LRA are more than my family at home (…) the relation was really strong, stronger than my real [biological] brothers. I might have helped some person in battle who was on the verge of death, protecting them from death – something that my real [clan] brother won’t do. Even at home, if I was on the verge of death, he wouldn’t do it, but [instead] run away and leave his own brother. But in the lum, people helped each other to the final moment. So today, so many [who knew me from the lum] come to see me, and want me to visit them in their homes. But you’re not invited in the same way from your family who live elsewhere. So the bond in the family relations in the lum is stronger than it is here.

Musa’s anger at his clan kin, and nostalgia for his LRA kin, was in part fuelled by their denial of his claims to land. But such nostalgia was not unmeasured. Musa had deserted the LRA after suspecting other rebels of concocting a plot to have him killed. His attachment to LRA kin was made all the more remarkable by the mistrust this plot stirred in him.

Musa claimed new kinship ties with his former LRA comrades, as though they were a clan of their own (as Makamoi alludes to, in the epigraph to this section). But he insisted that he gained more than just concrete social relations while a rebel – he gained the capacity of sociality itself. ‘[With the LRA, I learned how to] stay with people. Socialising together with people of different areas – we stayed with people there from different areas and walks of life, as brothers (…) I also learned to live together with [different] tribes, making me know how to socialise with people.’

Like Musa, others maintained relations with fellow rebels who had returned from the frontlines, even as physical distances often kept them apart. ‘The relationships (wat) in the lum are stronger than the ones here [biological kinship],’ Gunya declared. Within town, whenever another rebel friend of mine, Aliya, met with or ran into another former rebel woman, she greeted her as sister (lamego), a practice she explained as a result of the LRA spirit of togetherness (cwiny me bedo karacel). She, too, recalled how people in the lum supported each other as though they were blood family, and that many of these networks of support were maintained after their return from the frontlines. In her own family in the lum, when her husband was not around, his brothers would help their family with what they needed, providing them with cooking oil and other supplies. At gang, she lamented, a husband’s brother refused to help. People had lost their sense of helping each other, she mourned, working only as individuals. She saw this as an effect of the war – people had become poor and kept what little they had within their families, unable to maintain larger patronage networks.

This unity among former LRA rebels was partly an effect of rules and regulations that, many friends noted, controlled problems that were frequently troublesome at gang, including adultery and jealousy (nyeko) among co-wives. It was also a transformation of belonging that included a break from one’s clan kin as part of the process of becoming rebels. While they were in the lum, Gunya explained, they ‘didn’t know’ their relatives at gang. ‘People at gang know that even if you are a relative to a rebel (adwii), you shouldn’t get close to him,’ she said, meaning that rebels did not always hesitate to injure or kill their clan kin if they had to. One friend, Labwor, spoke of his gun as his mother and his father, the weapon often trumping the ties to his clan kin. Labwor’s friend Otto, also a former rebel, similarly referred to his gun as his mother, his wife, his everything – because with it, he was able to provide for himself and others through its force, robbing food and supplies, among other bad behaviours (bwami).

As these new relations of rebel kinship were established among men and women who had been conscripted against their will, blood itself came to embody these ties and mark them off as different kinds of biological kinship. Gunya once complained to me that her son would often run into the lum near their home on the outskirts of Gulu town whenever he was criticised or disciplined. She joked that dealing with children who were born in the lum was very hard. She said that her son had bush blood (remo me lum) or rebel blood (remo pa adwii). At first, I thought she was speaking metaphorically, but she explained, ‘people in the lum have a different blood from people at home.’ She recalled that when their son was young, she took him to the hospital to have an operation on his left knee, from which, she claimed, they removed ‘bullet acid.’ She wondered if the bullet wounds that she and her son’s father suffered in the lum had been transmitted to their child. ‘The blood of the parents is the one that makes the blood of the child. Both of his parents were adwii, and now he is too. He has adwii blood – that is why he runs to the lum,’ she concluded. Indeed, she suggested that he might one day become a fighter himself, either as a rebel or an army soldier. ‘The child takes to the idea of fighting as the parent did,’ she explained of the inheritance of a martial character. Not only had rebel kinship come to challenge clan kinship, establishing new patterns of mutual care, but it had slowly taken on the very form of shared blood. Importantly, this was not a kinship of brothers and sisters who had signed up to fight together with a shared vision and common goal. Rather, it was a kinship that emerged from a so-called crime against humanity – the forced and often random conscription of soldiers who, by and large, had no intention to fight.

Rebel Kinship beyond Humanity

In and through so-called crimes against humanity such as forced marriage and forced conscription, the LRA redrew relational boundaries to create what we could broadly categorise as rebel kinship. Rebels became husbands, wives, brothers, sisters, and children, cared by and caring for each other. As a form of mutual belonging, rebel kinship challenged and often overtook conventional relations – as exemplified in Mohammed becoming Onen’s brother at the expense of his birth brothers.

These relationships show that violence is not exclusively something destructive that must be coped with or survived, as Carolyn Nordstrom (1997) claims, but can also be creative, producing new forms of mutual belonging. Here, I follow Lubkemann (2008), Thiranagama (2011), and Ferme (2013) in questioning Nordstrom’s argument. Like the violence of heroin addiction described by Angela Garcia (2010) in the Española Valley in New Mexico, the violence of the LRA war destroyed certain relationships but also constituted others. When the causative violence is characterised as ‘against humanity,’ however, it becomes very difficult to understand the meaning within or produced in the aftermath of the violence. This is not to say that the violence itself was moral, nor that forced conscription and marriage was something positive to be accepted or lauded. Rather, it is to recognise that understanding the violence and its consequences through the static moral framework of humanity limits an understanding of life itself, and in particular, the perhaps unexpected turns it often takes over time after violent events.

Acknowledgements

My principal debt remains with those former rebels and their families who shared their lives and stories with me. I am grateful to Jimmy Odong for his camaraderie and intellectual curiosity. Thanks to Vincanne Adams, Lioba Lenhart, Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Jason Price, Susan Reynolds Whyte, and an anonymous reviewer for their invaluable reading of earlier versions of this article. The project from which this article draws was financially supported by the National Science Foundation, with whom I was a graduate research fellow from 2012 – 2015 while a doctoral student in the joint medical anthropology programme of the University of California-Berkeley and the University of California-San Francisco. This research was approved by both the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology and the School of Health Sciences at Makerere University, where I was a research affiliate of the Makerere Institute of Social Research (MISR).

References

Allen, Tim & Mareike Schomerus (2006). A Hard Homecoming: Lessons Learned from the Reception Center Process in Northern Uganda. Washington, DC: Management Systems International.

Annan, Jeannie, Christopher Blattman, Dyan Mazurana & Khristopher Carlson (2009). Women and Girls at War: “Wives”, Mothers, and Fighters in the Lord’s Resistance Army. HiCN Households in Conflict Network, Working Paper 63. Brighton: The Institute of Development Studies.

Baines, Erin (2014). ‘Forced Marriage as a Political Project: Sexual Rules and Relations in the Lord’s Resistance Army.’ Journal of Peace Research 51(3): 405-417.

Carlson, Khristopher & Dyan Mazurana (2008). Forced Marriage within the Lord’s Resistance Army, Uganda. Somerville: Feinstein International Center.

Dolan, Chris (2009). Social Torture: The Case of Northern Uganda, 1986-2006. New York: Berghahn Books.

Ferme, Mariane (2013). ‘“Archetypes of Humanitarian Discourse”: Child Soldiers, Forced Marriage, and the Framing of Communities in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone.’ Humanity 4(1): 49-71.

Garcia, Angela (2010). The Pastoral Clinic: Addiction and Dispossession along the Rio Grande. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lubkemann, Stephen C. (2008). Culture in Chaos: An Anthropology of the Social Condition in War. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

McKay, Susan & Dyan Mazurana. (2004). Where are the Girls? Girls in Fighting Forces in Northern Uganda, Sierra Leone and Mozambique: Their Lives During and After War. Montreal: Rights & Democracy, International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development.

Nordstrom, Carolyn (1997). A Different Kind of War Story. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Thiranagama, Sharika (2011). In My Mother’s House: Civil War in Sri Lanka. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.