Kamila Krygier

Department of Sociology and Social Policy, Lingnan University, Hong Kong

Abstract

People with mental health problems constitute a particularly vulnerable group, whose rights have been and still are abused and violated all over the world. The challenges are amplified in post-conflict regions of developing countries, where the prevalence of mental illness has been found to increase drastically. The present study takes the example of northern Uganda to examine the extent to which international human rights law is reflected in the daily lives of the rural communities.

The findings indicate that service provision is inadequate in terms of quality and accessibility. There is widespread discrimination against and abuse of people with mental health problems and little is done by the government to combat the common prejudices, raise awareness or assist the families with mentally ill relatives—all state obligations under the human rights treaties ratified by Uganda. Finally, it is argued that the existing international law itself is inadequate to cater for the unique situation of people with mental ill-health.

Background

Introduction

The field of mental health and mental illness has always been and still is a realm of serious and often disastrous human rights violations (Porter 2002: 4-9). Although the right to health, which explicitly refers to physical as well as mental health, is part of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (UN 1966), one of the earliest human rights documents, most countries, including those in the North championing these rights, have been equally complicit in abusing and violating them. It is important to note, however, that over the last centuries, and particularly decades, there has been considerable improvement with regard to the human rights situation of people with mental ill-health. In many countries new legal documents safeguarding the rights of people living with mental illness replaced the old ones, which frequently used abusive language and provided opportunities for mistreatment rather than legal protection (Lawton-Smith & McCulloch 2013: 1-10). Furthermore, new international human rights documents have been developed which are supposed to address this group more specifically, such as the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (UN 2006) or the Guidelines for the Promotion of Human Rights of Persons with Mental Disorders (WHO 1996).

Despite the above-mentioned positive developments, the situation of people with mental health problems is still rather dismal in most parts of the world. In particular, poor or developing countries struggle to provide adequate or sometimes, in fact, any care at all (Kohn et al. 2004: 858-866; Read, Adiibokah & Nyame 2009). A post-conflict setting aggravates the existing challenges. In some countries, where service provision existed previously, the infrastructure got destroyed during the conflict and in places where mostly the community cared for the mentally ill, the destruction of the social fabric leaves this group more vulnerable than ever (Sayon 2011; UN Peacebuilding Programme 2011: 4). Moreover, mental health rarely appears to be an immediate need as the inadequate provision of this type of care does not seem as serious or life-threatening. At the same time it is known that mental disorders, in particular post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression, increase considerably as a result of violent conflicts (de Jong et al. 2001: 555).

Uganda provides an example for most of the described challenges. It is a developing country with a long history of violent conflicts. Various studies have found an extremely high prevalence of PTSD and depression within the population of northern Uganda most affected by conflict (Vinck et al. 2007: 543; Roberts et al. 2008).

Conflict and mental illness in northern Uganda

Northern Uganda is right now in the process of recovering from a decades-long conflict, which formally ended in 2006. The war between the rebel movement, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), and the Ugandan national army was characterised by countless atrocities, mutilations and abductions of children, many of whom were turned into child soldiers. The main victims, the civilian Acholi population, were forced into internally displaced people’s (IDP) camps which, instead of protecting them, rather added to their ordeal (HURIPEC 2003: 8). The multiple exposures to traumatic events and the lack of a secure and conducive environment for victims of violence have been found to contribute considerably to a later development of PTSD (de Jong et al. 2001: 556). Therefore, it appears that the prevalence of mental disorders, in particular PTSD and depression, can be attributed to a large extent to the conflict, the living conditions and experiences of the population of northern Uganda during, as well as after, the war, even though comparative statistics from the time before the conflict are not easy to obtain (Amone-P’Olak et al. 2013: 8-10).

International and national human rights law and mental health in Uganda

Uganda has signed and ratified the international human rights treaties that guarantee the rights of people with mental health problems. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), including article 12, which deals with the ‘right to health’, was ratified by Uganda in 1987. The right to health aims to ensure the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

In 2008, Uganda ratified the Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (CRPD), another human rights treaty dealing with the rights of people with mental ill-health (UN 2006). The CRPD emphasises the respect for dignity, individual autonomy including the freedom to make one’s own choices, the independence of persons, non-discrimination, full and effective participation and inclusion in society, respect for difference and equality of opportunity. The ratification of international human rights treaties renders them legally binding in Uganda and, therefore, the fulfilment, respect and protection of its articles is a state obligation.

Ugandan national law, on the other hand, lags behind these signed and ratified international documents. The current law regulating the status and treatment of people with mental health problems in Uganda is the outdated and offensive Mental Treatment Act 1964. The new mental health bill, developed to address the shortcomings inherent in the Mental Treatment Act 1964, remains a bill and has not been passed by parliament into law for several years now.

The present study aimed to assess the human rights situation of people with mental ill-health in northern Uganda with regard to service provision and the attitudes of the communities. One of the questions is: To what extent is human rights legislation being implemented to secure the situation of people with mental health problems in this region?

Methods

Survey sites and participant selection

The data collection for this study was carried out in the Lango and Acholi sub-regions of northern Uganda over a period of two weeks in 2013. The districts were selected by convenience, based on their location, while the selection of sub-counties within the districts was randomised. However, in cases where the nearest health facility was located in another sub-county, this health facility was visited. The surveyed sub-counties in the districts of Gulu, Amuru, Lira and Oyam included: Awach and Koro in Gulu; Amuru and Pabbo in Amuru; Lira, Amach and Ogur in Lira; and Aber, Loro and Oyam in Oyam.

The health care system in Uganda is hierarchical. It starts from the lowest village level, at which local village health teams (VHTs) with very basic health training operate, followed by health centre II, health centre III, health centre IV, district hospital, regional referral hospital and finally a national referral hospital. On each level there should be a specific category of professionals present with a defined level of knowledge on mental health (see Chart 1).

The research teams visited all health care levels within the selected geographical areas. Additionally, the national mental health referral hospital, Butabika, was surveyed, since it is the major mental health facility in the country and admits people from all regions of Uganda.

The participants in the study included health workers at all levels of the health care system, namely: village health team members, persons in charge of health centres II, III and IV, clinical officers, nurses, social workers, psychiatric doctors, clinical psychologists and occupational therapists at the district, regional referral and national referral hospital levels. Whenever available, private health facilities, such as hospitals, were also included. Furthermore, district officials, Local Council (LC) I[2] chairpersons, traditional healers, people with mental health problems as well as their relatives and caretakers, were also interviewed as key informants. Community members participated in the focus group discussions. Finally, the Principal Medical Officer in charge of Mental Health and Substance Abuse at the Ministry of Health was interviewed. The total number of participants in this study was 329, with 313 from northern Uganda and 16 from Kampala, with the latter either working at the national referral hospital or the Ministry of Health. Gender balance was observed, particularly during the focus group discussions, while other respondents were selected on the basis of their roles. Moreover, to prevent biased responses, participation in focus group discussions was strictly limited to people not directly affected by mental illness; for instance, the participation of relatives of a person with mental health problems in a focus group discussion could potentially influence the responses of the other group members. People affected by mental illness were instead interviewed individually as key informants.

Chart 1: The health care system in Uganda

Research design and instruments

The research design was a descriptive mixed-method study combining literature review, the quantitative survey approach with semi-structured key informant interviews and focus group discussions. The mixed-method approach allowed establishing the prevalence and frequency of certain opinions or beliefs through a survey methodology, while the open questions contributed to a deeper understanding of perceptions and attitudes. Individual interview guides were developed for each group of respondents.

A member check was applied in order to increase the validity of the study by presenting and discussing the outcomes of the study with selected groups of respondent representatives.

Results

Is mental illness a community concern?

A number of studies carried out during or immediately after the conflict found extremely high levels of PTSD and depression among the affected populations of northern Uganda (Vinck et al. 2007: 549; Roberts et al. 2008). Some newer studies indicate psychological long-term effects and poor functioning of the war-affected youth in the Acholi sub-region (Amone-P’Olak et al. 2013: 7). The above-mentioned studies, however, did not specify if this was perceived by the communities as a serious issue and how they estimated the extent of the prevalence of mental illness cases.

Therefore, the LCIs of the surveyed villages were asked if they saw mental health as a serious concern.

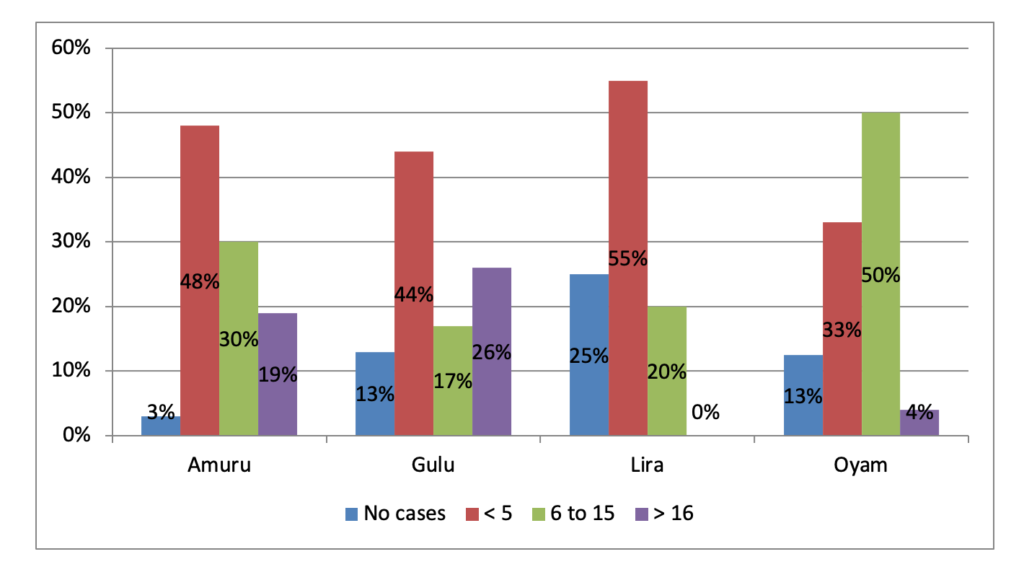

Out of 47 LCIs, 43 were of the opinion that mental health was a serious concern. Further, LCIs and village health team members (VHTs) were asked to estimate the number of cases of mental illness in their respective villages. While the majority of respondents reported some mental illness cases in their villages, Gulu and Amuru reported the highest numbers, with 26% and 19% respectively estimating the number of cases in their villages as being 16 or above (see Chart 2).

Chart 2: Estimated number of mental illness cases by VHT members and LCIs

Further, the participants in the eight focus group discussions perceived mental health as a critical matter and some even described the numbers of people suffering from mental illness as alarming.

The numbers are alarming. [There are] 11 [cases] in our village, but 50 in the parish.

There is quite a number of cases and then it becomes a concern for the whole community.

Mental health service delivery—quality and accessibility

The ‘right to health’ aims to ensure the ‘highest attainable standard of health’ for all people with regard to physical and mental health. How, therefore, is the quality of service delivery in the field of mental health? And how is the perceived accessibility to those services in northern Uganda?

Different studies and articles described mental health service delivery as deficient. The various challenges described included lack of qualified staff and inadequate provision of drugs, abusive treatment of patients by health care professionals, and the general underfunding of the whole mental health sector (Kigozi et al. 2010: 3, 5-6; Cooper et al. 2010: 581; Baingana & Mangen 2011: 291). The situation in upcountry facilities is even more deplorable, especially since of the 1% of health funds dedicated to mental health 55% goes to the national mental health referral hospital, Butabika (Kigozi et al. 2010: 3). The Acholi sub-region, despite its high prevalence of mental illness, is no exception, according to a UN study from 2011 (UN Peacebuilding Programme 2011: 16).

Personnel at all levels of health facility were interviewed and patients and caretakers were asked for their assessment. People affected by mental health problems, such as the service users themselves, the caretakers and family members interviewed for the present study, varied in their subjective assessment of the quality of the available services. This might be due to the personal differences regarding the understanding of what ‘good services’ mean. For example, though the majority of this group of respondents perceived the services as ‘good’, less than half of former patients felt they had been treated with respect and dignity. It appears as if respectful treatment is perceived as a luxury, rather than as something that should be expected or even demanded and that should definitely constitute a fundamental part of good quality service delivery. One mental health service user described her stay in a mental health facility:

Cleaners [are] pouring water on patients or punishing those who delay to wake up like locking them in bathrooms or chasing them to stay in cold.

Other reported challenges are inadequate supply of drugs and insufficient information provision for patients and caretakers. One mental health worker in Gulu Regional Referral Hospital explained the reasons for inadequate amount of drugs:

The drugs, especially the modern ones, are expensive and it is not perceived as sustainable, since patients have to take them for long or forever. The same amount can buy many other drugs, [for example] for Malaria.

In extreme cases the lack of information can have tragic consequences, as narrated by a health professional interviewed at the Gulu Regional Referral Hospital:

A mentally ill girl has been discharged from the hospital upon insistence of her family and given drugs to take at home. One of the side effects of the drugs has been an extreme swelling of the tongue. The family tried to push the tongue back inside the mouth and after failing they decided to visit a witchdoctor, thinking it must be witchcraft. The witchdoctor also failed but in the course of trying to push the tongue back in it got infected and the girl died from the infection.

In addition to the above-mentioned challenges, the caregivers also reported hostility and lack of support as the challenges they faced while caring for their ill relatives.

Table 1 summarises the most common responses by 114 respondents from communities and the health sector regarding the major challenges in accessing treatment.

Table 1: Challenges in accessing formal treatment[3]

| Response | Frequency |

| Lack of drugs | 58 |

| Distance to health facility | 38 |

| Family negligence | 28 |

| Lack of skilled staff | 28 |

| No challenges | 14 |

| Preference for witchdoctors | 7 |

| Staff absenteeism | 7 |

As can be seen in the table above, the second biggest perceived problem is the distance to the health facilities. This directly addresses the second question of accessibility of health services. For many poor people in rural settings, even reaching the next health centre can be extremely hard without transport and, moreover, accompanying a possibly difficult patient; accessing the more qualified services at Gulu Regional Referral Hospital is even more problematic.

The immediately available first level of health care services, the village health teams (VHTs), mostly lack even basic knowledge of mental health. Almost half of the interviewed VHT members have not received any training in mental health. The ones who reported to have received training stated that it was mostly in counselling. The required type of staff (see Chart 1) with professional knowledge of mental health seems to be mostly present at health centre (HC) IV level. At the four HCs IV visited, all informants reported that they had had some specific training in mental health. At the HCs II and III levels, the required type of professional staff was present in three-quarters and half of the cases respectively.

However, even at the regional referral hospitals the situation is not satisfactory. At the time of the study there was reportedly only one psychiatrist in northern Uganda; and it emerged from a recent presentation by Dr. Sheila Ndyanabangi, the Principal Medical Officer in charge of Mental Health and Substance Abuse,[4] that the total number of active psychiatrists in Uganda is 28, for a population of over 30 million.

Only a few respondents mentioned the preference for witchdoctors as a challenge. Possible reasons are that a number of people do not perceive this as a challenge or traditional healers and witch doctors are less frequently visited than generally assumed. In fact, though the health professionals interviewed stated that visiting traditional healers or witchdoctors was the first recourse for people in rural communities, this could not be verified through interviews with community members themselves or even with traditional healers, so it appeared to be less common than generally believed.

The assessment of private services was even more unsatisfactory. The facilities visited had very rudimentary mental health services or none at all. Though a few NGOs offer some support, the access to quality services is highly inadequate and the non-governmental facilities and organisations contribute very little to improving the situation.

Finally, the mental health professionals were asked about the existence or extent of legal protection of patients severely mistreated by family or community members and reporting to a health facility in a state clearly indicating abuse or neglect. It turned out there are no official guidelines for health staff to deal with such cases, which means that the decision on how to best protect the rights of the patients and, indeed, if to take any action at all is left at their discretion.

Mental illness at community level—beliefs, attitudes and family care

The second objective of the study, apart from health care service provision, was to assess the daily living situation of people with mental health problems. What are the perceptions and beliefs with regard to mental illness? Is there widespread discrimination and stigma generally surrounding this group of people (Corrigan & Watson 2002: 16)? And what are the initiatives undertaken by the state to ensure the protection of the rights of people with mental ill-health?

The common themes that emerged from the narratives of family members, people with mental health problems and community members emphasised widespread stigma, mistreatment and exploitation. Several of the LCI’s reported particular cases of mistreatment:

They are insulted, neglected, tied up and beaten. They are not well treated in the community, although some people are kind and feed them.

One respondent with mental health problems reported:

I was beaten constantly by my brothers because they considered me useless.

Some families reject the burden straight away, abandoning their ill relatives, while others tried to cope with the challenge by locking them up. Another LCI reported:

A girl born with mental illness was left by her family. Now she has to beg for food from other homes.

A number of families, however, struggle at first to provide for their mentally ill relative, especially in the case of children. In many cases those families face hostility from neighbours and experience a complete lack of support, a situation, which overwhelms them and renders appropriate family care impossible. According to the interviewees’ reports, most families end up abandoning their ill relative to a life on the streets.

Those with acute states of mental illness who live on the streets are completely helpless and unprotected from any form of verbal or physical abuse. A participant of one FGD said:

People do not like them. Mentally ill people are always abused each time they appear in public. This results in fights. Others are feared or isolated. (…) Some attempt to rape women (…). [They are] seen as people who are less important because they don’t bathe. Not allowed near others, sent away.

Many women experience sexual abuse and rape and some get pregnant, hence perpetuating the vicious circle of poverty, abuse and discrimination over generations. Mostly, they are not in a position to report the crimes committed against them, and in the rare cases where they get support, for example from NGOs, the cases are not taken seriously and not followed up. As one respondent from a local NGO reported:

There has been a child defiled in Bungatira. She was 13 years old and mentally ill. No one bothered about her. Even the police did not take action. (…) We took the case to the police and they said they will follow it up but they did not. People with mental illness are not taken seriously by the community or by the law. They cannot access legal help. These days even clan leaders are not bothered.

In one of the sub-counties visited, incidents involving the rape of mentally ill women were so rampant that most left the area. Many respondents stressed that the most excessive forms of abuse were mainly perpetrated by youth and that elderly people were generally more empathetic and understanding.

There are, however, also positive examples of supportive families or communities showing sympathy. According to one LC I:

Some are well taken care of, engaged socially [for example] in football games, offered compassion or food (…)

And some caregivers reported acceptance and understanding on the side of the community:

People don’t mistreat her because they feel sorry for her.

People in the community have accepted him the way he is.

Mothers, especially, often strive to take care of and protect their mentally ill children.

Many families see them as useless [lac ma owing, ‘spoilt sperm’]; they give them a piece of clothing and some food and don’t want them to get lost or die of negligence because they fear a curse for the family. Mothers take better care, men do not care.

It seems, however, that discrimination and mistreatment are far more common.

Another form of abuse highlighted in one of the focus group discussions was work exploitation, whereby people with mental health problems are made to do hard labour and are afterwards chased away without payment.

[There are] also cases of exploitation. [They are] made to work in the field for free and then chased.

Sometimes mentally ill people are cheated by others, as one caregiver reported:

People refer to him as a mad man, which makes him turn violent. People cheat him at the shop during the exchange of money. Sometimes he gives more balance. People take advantage of him.

An important factor contributing to stigma of people with mental ill-health could be the limited knowledge or misinformation about the nature of mental disorders, especially in rural regions. One caregiver narrated the history of mental illness in her family:

The great grandmother brought home a boy and took care of him. The boy was slaughtered by the brother of the great grandfather. He did not die immediately but later died from the injuries. The family never compensated the death of the boys’ family. Therefore mental illness is occurring. Even the brothers of the patient suffered from it, but since this occurred to the father’s side of the family and the father is dead, so one must take the responsibility and compensate the family.

Traditional or supernatural beliefs are often mixed up with a Western medical approach or religion. For example, a number of respondents suggested vaccination to prevent the occurrence of mental illness. Others linked the aggression towards mentally ill people with the belief that their illness can be transmitted, as reported by two different LCIs:

Some attack them violently for fear their illness can be contagious.

The mentally ill people are suffering in many cases from violent attacks because of fear the illness can be transmitted.

Table 2 below summarises the most common responses by 157 respondents regarding the causes of mental illness.

Table 2: Community perceptions of causes of mental illness

| Response | Frequency |

| It is the result of past experiences | 54 |

| It is inherited | 52 |

| It is due to witchcraft | 32 |

| It is like any other illness | 27 |

| It is a curse | 25 |

| It has a supernatural cause (unburied bones, spirits) | 21 |

Of the 157 respondents, 40.8% (64 persons) believed in some sort of supernatural cause of mental illness. It is possible that the number is even higher in the average rural population, since the respondents here included people with mental health problems, their relatives and caregivers as well as VHT members, i.e. people expected to have better knowledge of mental illness owing to their personal experiences. This assumption was underpinned by responses from the focus groups discussions, in all of which beliefs about supernatural causes of mental illness were mentioned.

The general ignorance on the part of the scientific community regarding local beliefs and understanding of mental illness is an additional problem. Though some studies have been conducted that try to understand and describe the perceptions and categorisation of mental disorders in the Acholi sub-region, those attempts are rather isolated and limited (Betancourt et al. 2009: 6-7). Mostly, effort is made to replace the traditional beliefs with Western medical terms, which contrast considerably with the spiritual understanding and worldview of local communities.

While knowledge about mental health is not common, initiatives for community education are also almost non-existent. 107 respondents, including LC1s, VHT members and people with mental ill-health, were asked if they were aware of any community education on mental health carried out in their village. Only 19 responded positively, which constitutes 17.7 % of the population studied. Moreover, the majority of those educational activities were carried out by NGOs and in only a few selected cases was a government institution involved. Most of the reported education activities were carried out in Gulu District, followed by Amuru and Lira Districts, with the fewest in Oyam District.

The mental health focal person of one of the districts studied admitted that although community education should have been one of his duties, no budget was attached to the position or assigned for educational activities. The same challenges have been reported by health professionals at the regional referral hospital. At the same time a number of respondents stated that in cases where community education had been carried out, the treatment of people with mental health problems by community members improved considerably.

In conclusion, it can be stated that people with mental ill-health are left to the mercy of their families and communities. If they are lucky enough to be in a supportive environment their chances of recovery and survival are much higher. The less lucky ones remain unprotected, without help or assistance, and prone to fall victim to any form of abuse and mistreatment, which, moreover, mostly goes unpunished.

Situation of mental health professionals

The stigma surrounding mental illness clearly emerged from a number of the articles cited above as well as from the present study. This leads to the following questions: How do mental health professionals perceive their situation? Do they also experience stigma or discrimination?

The majority of the health workers interviewed stated that the situation of mental health professionals is in many ways different from the work and general conditions in other health care sectors. Some described the differences in positive terms, explaining that, since the diagnosis and treatment were more complex and required more personal expertise based on the knowledge and assessment of the medical staff rather than on machines or equipment, mental health professionals were very skilled and experienced.

However, of the 20 mental health professionals working in the mental health unit of Gulu Regional Referral Hospital or at the National Mental Health Referral Hospital, Butabika, 12 stated that the general population and even their fellow health workers mostly perceived them as being no different from their patients. One psychiatric nurse in Butabika explained:

Many people think that to look after the mentally affected people one has to have some degree of mental illness.

Some felt that they were not taken seriously and that their unit received less attention, funds and resources than others. One respondent pointed out that, owing to the widespread stigma attached to mental ill-health, many of her colleagues chose this profession only if they had no other option.

They always make fun of us that we are like our patients. Even very few take it up as their profession. Many just do it if they don’t have any other choice—not voluntarily.

In addition to this widespread stigma, the work conditions of mental health workers are extremely difficult. There are not many special security provisions, neither for patients nor for the professionals. A number of unproven anecdotal incidents have been reported in the course of this study, in which mental health workers were severely attacked by the patients.

Obviously, those difficult and not very conducive working conditions, combined with the negative stereotypes surrounding this field of work, do not make the profession of a mental health worker very appealing. Hence this contributes to the lack of adequate human resources in the area of mental health in Uganda.

Discussion

So how does the reality of northern Uganda relate to the international human rights treaties ratified by the country?

Apart from the already mentioned article 12 of the ICESCR that deals with the ‘right to health’, in 2008 Uganda also ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). The term ‘persons with disabilities’ includes people with long-term ‘mental impairments’ (UN 2006). The convention stipulates, among others, equality and non-discrimination, access to justice, freedom from torture and cruel treatment as well as the state’s obligation to raise awareness and educate its citizens. Moreover, the convention emphasises the special situation and the resulting need for protection of women and girls with disabilities. The convention obliges states to assist people with disabilities living in a state of poverty. The state is also compelled to collect statistics and data regarding people with disabilities in order to be able to design appropriate policies.

Obviously all of the above-mentioned obligations are not fulfilled. There is widespread discrimination, even extending to professionals working in the field, and the state does not provide the awareness-raising and education on the topic stipulated in the CRPD. There is no protection from cruel and inhumane treatment and limited access to justice for the victims. The women, who are frequently subjected to rape and sexual abuse, do not enjoy any kind of protection and no particular assistance is provided for people with mental health problems living in a state of poverty. Since the reciprocal relationship between poverty and mental illness has been highlighted by other authors, such assistance would be especially crucial (Ssebunnya et al. 2009: 4).

Data collection is another important point to be highlighted separately, as this might not be an issue commonly expected to be included in a human rights treaty. Taking the present example of northern Uganda, it becomes apparent why such measures might be important. Most of the people interviewed believe that the problem of mental illness is particularly severe in the North. There have also been a number of studies, mentioned previously, which point to a very high prevalence of certain disorders in this region. There are, however, no official statistics in this regard. Even Uganda’s only national mental health referral hospital, Butabika, does not keep statistics regarding the regions the patients come from, as admitted by the employees surveyed for this study. Knowing that certain illnesses are particularly common in some areas would help in extending specialised services and drug provision. However, as long as such information is not collected, the kinds of services that are most necessary as well as the budget implications become difficult to determine. The need for more services in the field of mental health in northern Uganda as well as that for more data has been a clear result of our study and also something emphasised by other scholars (Amone-P’Olak et al. 2013: 9).

It has to be noted that the development of the Mental Health Bill 2011 was a clear step towards the fulfilment of some of the obligations. The bill, however, remains a draft to-date. It is not clear if and when it will finally be passed into law.

The inadequate realisation of the obligations arising from the ratification of the international treaties is, however, only part of the problem. Also, the international treaties can be perceived as generally insufficient to offer the necessary protection of the human rights of people with mental health problems. Of course it could be argued that the basic human rights treaties clearly state that human rights are inherent rights of all people irrespective of origin, sex, age or their state of health. In the history of international human rights legislation it has been recognised, though, that certain groups are more vulnerable than others and, therefore, need additional protection, as reflected in specific documents developed on their behalf. This is how treaties dealing with the rights of women (Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women), the rights of children (Convention on the Rights of the Child) or the previously described Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities came about. Clearly, people with mental health problems are a particularly vulnerable group who need specific consideration, and not only in developing countries. They have distinct challenges, which need to be taken into account and addressed separately in order to adequately ensure their enjoyment of their human rights. The CRPD, though it can be perceived as a step forward, does not satisfy or fulfil those requirements.

First, a problem exists with the groups of people it is meant to address. ‘Long-term mental or intellectual impairment’ does not cover all forms of mental health problems, apart from the fact that ‘long-term’ is also not clearly defined in this context. Second, even if this formulation had been rectified, it could still be argued that people with mental health problems need to be considered separately from people with physical disabilities, who not only face challenges of a different nature in their daily lives but are also perceived differently by the general population. Finally, combining those diverse groups can amplify the discrimination of people with mental ill-health. The perception that the CRPD already caters for the situation of people with mental health problems might obscure the fact that it is insufficient and does not take into account the distinctiveness of their circumstances as well as the stigma they face. For example, as has been admitted by the Principal Medical Officer in charge of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, Dr. Sheila Ndyanabangi, though persons with disabilities, the group under which people with mental ill-health are subsumed in Uganda, are entitled to official representation in the government in order to make their voice heard, people with mental health problems are discriminated against within this group and rarely get elected into such positions of political influence.

Limitations of the study

The study has a number of limitations. Since the focus was on describing the situation of people with mental health problems from the human rights perspective, the types and categories of the mental disorders have not been and could not be established. This kind of categorisation is difficult in itself owing to the differences that exist between the local understanding of mental illness and Western diagnostic systems. Further, the geographical coverage was limited owing to time and funding limitations.

Finally, it is important to point out that all statements rely on the perceptions of the respondents interviewed. As reliable statistics are one of the challenges highlighted in the results, those perceptions or estimates could mostly not be verified through official sources. For example, the assessment of the prevalence of mental illness cases is an estimate by the interviewees; also, though other studies emphasise a high percentage of depression and PTSD, the numbers presented in this study should be seen as supporting the conclusion that mental health is a concern for the communities and not as absolute numbers or facts.

Conclusion

The human rights of people with mental health problems remain in a dire condition all over the world but particularly in poor developing countries, and even more so in post-conflict settings. The example of Uganda clearly demonstrates that the ratification of the relevant human rights treaties does not guarantee any improvement in real-life conditions. First, the state does not fulfil its legally binding obligations towards people with mental health problems. While this is also true of other vulnerable groups, most do receive national and international attention and there are some steps being taken to rectify their situation. This is not the case with people with mental ill-health, who are mostly forgotten or neglected by international and national NGOs, donors and human rights organisations alike.

Second, the existing international human rights treaties are not sufficient to cater for the needs and challenges faced by people with mental health problems. Subsuming them under the group of people with disabilities does not do justice to their particular situation. Moreover, the formulation in the CRPD does not cover, in its current state, all groups of people with mental ill-health. For successful advocacy on behalf of the rights of people with mental health problems and for their voice to be heard, they need to be recognised and acknowledged as a distinct group under international human rights legislation.

References

Amone-P’Olak, Kennedy; Jones, B. Peter; Abbott, Rosemary; Meiser-Stedman, Richard; Ovuga, Emilio & Croudace, Tim (2013). ‘Cohort Profile: Mental Health following Extreme Trauma in a Northern Ugandan Cohort of War-affected Youth Study (The Ways Study).’ National Centre for Biotechnology Information 2 (300). Accessed May 17, 2015. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-2-300.

Baingana, Florence & Mangen, Onyango Patrick (2011). ‘Scaling up of Mental Health and Trauma Support among War-affected Communities in Northern Uganda: lessons learned.’ Intervention 9 (3): 291-303. Accessed May 18, 2015. http://psychotraumanet.org/sites/default/files/documents/int_195.pdf.

Betancourt, S. Theresa; Speelman, Liesbeth; Onyango, Grace & Bolton, Paul (2009). ‘Psychosocial Problems of War-affected Youth in Northern Uganda: a qualitative study.’ Transcult Psychiatry 46(2): 238-256. Accessed May 20, 2015. doi:10.1177/1363461509105815.

Cooper, Sara; Ssebunnya, Joshua; Kigozi, Fred; Lund, Crick; Flisher, Alan & MHAPP Research Prog. Consortium (2010). ‘Viewing Uganda’s Mental Health System through a Human Rights Lens.’ International Review of Psychiatry 22(6): 578-588. Accessed May 16, 2015. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2010.536151.

Corrigan, W. Patrick & Watson, C. Amy (2002). ‘Understanding the Impact of Stigma on People with Mental Illness.’ World Psychiatry 1(1):16-20. Accessed May 17, 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1489832/.

de Jong, T.V.M. Joop; Komproe, H. Ivan; Van Ommeren, Mark; El Masri, Mustafa; Araya, Mesfin; Khaled, Noureddine; van de Put, Willem & Somasundaram, Daya (2001). ‘Lifetime Events and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in 4 Postconflict Settings.’ JAMA 286(5): 555-562. Accessed May 18, 2015. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=194062.

HURIPEC (2003). The Hidden War. The Forgotten People. Accessed May 21, 2015. http://allafrica.com/download/resource/main/main/idatcs/00010178:affb3b76075dd71c20d0b054b065bff9.pdf.

Kigozi, Fred; Ssebunya, Joshua; Kizza, Dorothy; Cooper, Sara & Ndyanabangi Sheila (2010). ‘Mental Health and Poverty Project. An overview of Uganda’s mental health care system: results from an assessment using the world health organization’s assessment instrument for mental health systems (WHO-AIMS).’ International Journal of Mental Health Systems 4(1): 1-9. Accessed May 18, 2015. doi:10.1186/1752-4458-4-1.

Kohn, Robert; Saxena, Shekar; Levav, Itzhak & Saraceno, Benedetto (2004). ‘The Treatment Gap in Mental Health Care.’ Bulletin of the World Health Organisation 82(11): 858–866. Accessed May 20, 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2623050/.

Lawton-Smith, Simon & McCulloch, Andrew (2013). Starting Today – Background Paper 1: History of Specialist Mental Health Services. Accessed May 22, 2015. http://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/content/assets/pdf/publications/starting-today-background-paper-1.pdf.

Porter, Roy (2002). Madness. A Brief History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Read, M. Ursula; Adiibokah, Edward & Nyame, Solomon (2009). ‘Local Suffering and the Global Discourse of Mental Health and Human Rights: an ethnographic study of responses to mental illness in rural Ghana.’ Globalization and Health 5(13), Accessed May 19, 2015. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-5-13.

Roberts, Bayard; Kaducu, Ocaka Felix; Browne, John; Oyok, Thomas & Sondorp, Egbert (2008). ‘Factors Associated with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Depression amongst Internally Displaced Persons in Northern Uganda.’ BMC Psychiatry 8(38). Accessed May 19, 2015. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-8-38.

Sayon, O. G. Morrison (2011). ‘Construction of Modern Mental Health Begins Soon… JFK adm. appeals to illegal squatters.’ Inquirer. Accessed May 20, 2015. http://theinquirer.com.lr/content1.php?main=news&news_id=966.

Ssebunnya, Joshua; Kigozi, Fred; Lund, Crick; Kizza, Dorothy & Okello Elialilia (2009). ‘Stakeholder Perception of Mental Health Stigma and Poverty in Uganda.’ BMC International Health and Human Rights 9(5). Accessed May 20, 2015. doi:10.1186/1472-698X-9-5.

UN (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Accessed May 17, 2015. http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml.

UN (1966). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Accessed May 17, 2015. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx.

UN Peacebuilding Program (2011). Mental Health and Peacebuilding in Acholiland; To love and to work: local understandings of post-conflict mental health needs. Kampala: UN Uganda.

Vinck, Patrick; Pham, N. Phuong; Stover, Eric & Weinstein, M. Harvey (2007). ‘Exposure to War Crimes and Implications for Peace Building in Northern Uganda.’ JAMA 298(5): 543-554. Accessed May 17, 2015. doi:10.1001/jama.298.5.543.

WHO (1996). Guidelines for the Promotion of Human Rights of Persons with Mental Disorders. Accessed May 21, 2015. http://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/legislation/guidelines_promotion.pdf.

[1] This article is based on research carried out in 2014 by the author and members of staff of the Research Department of John Paul II Justice and Peace Centre, Kampala, Uganda.

[2] Local Council (LC) chairperson I is the lowest administrative level (village level) in Uganda. The highest is Local Council (LC) V, which is the district level.

[3] The questions were formulated as open questions, providing participants the option of giving several answers. Therefore the combined number of responses for all categories is higher than the total number of respondents.

[4] Presentation at John Paul II Justice and Peace Centre, Kampala, for a mental health stakeholders meeting on 31 July 2014.