Paula Hirsch Foster:

Anthropology and Land Tensions in Acholiland, 1954-1958

By Martha Lagace

Department of Anthropology, Boston University, USA

Abstract

Paula Hirsch Foster, a Hungarian-born student from Chicago’s Northwestern University, conducted doctoral research in Acholiland between 1954 and 1958. Despite her fascination with Acholi life, her fluency in the language, and her promise as a scholar, Foster (1930-1997) never published her research or completed her PhD. Drawing upon the Paula Hirsch Foster Collection of field notes at Boston University’s African Studies Library, this research note introduces Foster and the collection. Its main contribution is to provide evidence that Acholi concerns about land alienation go back at least to the 1950s. Her field notes demonstrate that Acholi fears for their land are not new and not simply the result of the war between the government and the Lord’s Resistance Army.

‘In late 1954, a Ford Foundation Research Fellowship was granted to me to study the changing status and role of women in Acholi society ….’

So began the thesis outline of Paula Hirsch Foster, an anthropologist in the making. During four years of field research—nowadays an inconceivable luxury of time—Foster moved between West and East Acholi living in homesteads, mastering fluency in the language, and writing copious notes about everything she saw, heard, and experienced. For a while—how long is not clear—she also put her Acholi language skills to use as a court interpreter.

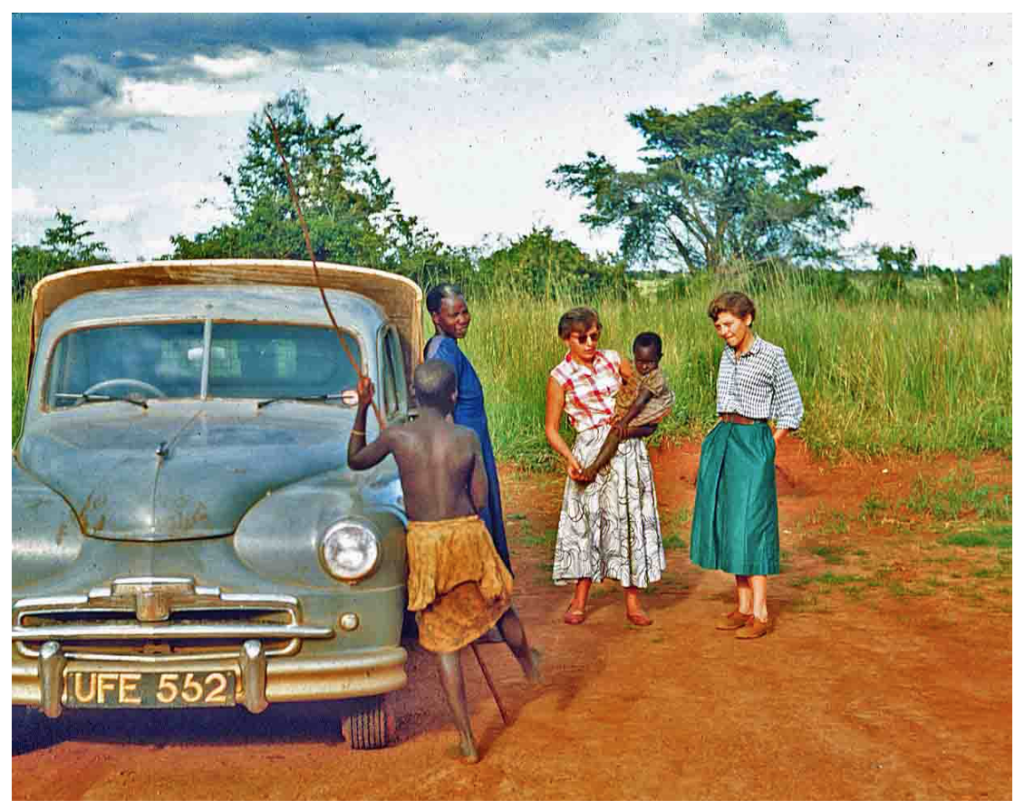

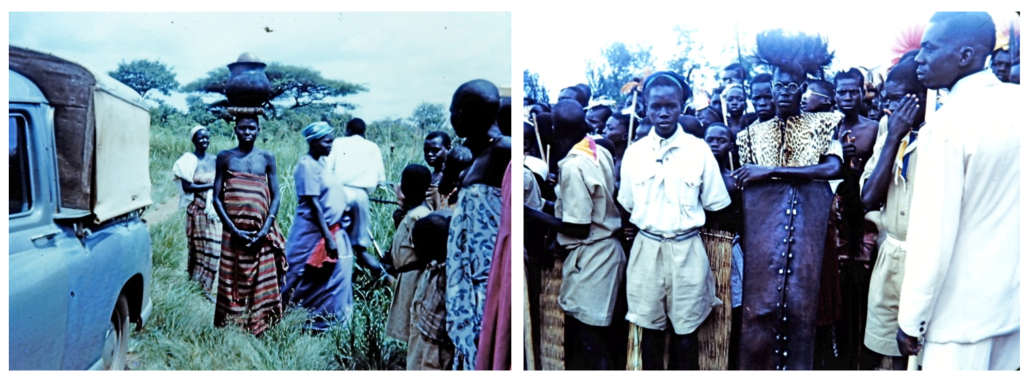

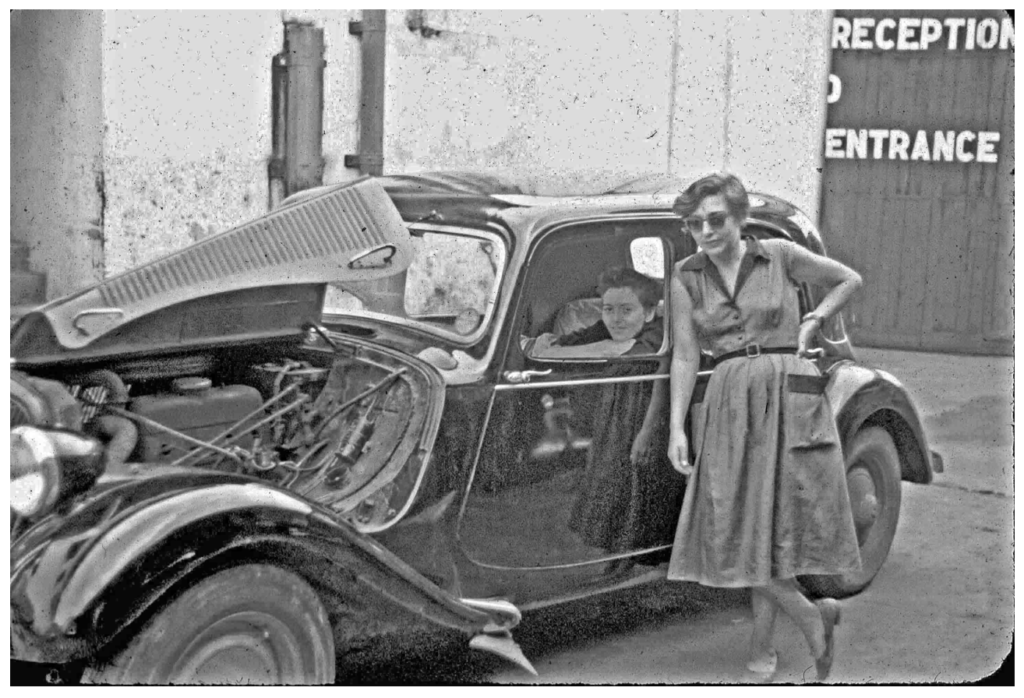

Foster traversed the physical distances in her rugged Opel van, usually giving a lift to locals. She attended funerals, dances, ajwaka divinations; interviewed male elders about Acholi principles, and schoolgirls about their own life stories. Even 60 years on, one can sometimes meet older men and women around Gulu town who remember her fondly or at least recall her Opel van rumbling past; and babies were named Paula after her. In that sense she made her mark.

Unfortunately, Foster never published the thesis or any other work about her time in Acholiland. This may be why her deeply researched, pioneering study has continued to slip under the radar of many contemporary scholars of Acholi. Nor did she attain her PhD degree—despite her absorbing interest in Acholi, her many personal and professional relationships there, and her promise as a scholar.

(Photo courtesy of Boston University Paula Hirsch Foster Collection)

This research note introduces readers to a remarkable woman and to the archive she left behind. Her notes, which fill 15 boxes at Boston University’s African Studies Library, may be accessed by scholars who visit in person; in the meantime a detailed finding guide is available on OpenBU or by email to asl[at]bu.edu. (The collection is currently being digitized.) Below, I include extracts of her notes to give a sense of the challenges she faced and to offer glimpses of Acholi culture and tensions in an era that was far less documented by anthropologists than the current post-civil war period. These extracts provide evidence that Acholi concern about the alienation of their land is by no means a new phenomenon.

Perhaps Foster’s refusal to complete her PhD thesis was due to factors that especially affected female students in the 1950s. First, as a woman she may have been expected to study women; but upon arrival she found other topics more compelling. It appears she aimed for a head-on comparison with the Nuer studies of E. E. Evans-Pritchard. Observations about women are there in her notes but are relatively few compared to other aspects of Acholi life: kinship, law, religion, suicide, jok rituals, witchcraft; discourses and struggles over land; and Uganda’s coming independence.

Second, according to different accounts, her thesis supervisor, the great Melville Herskovits, was a demanding personality and much older besides. Given that Foster was self-confident and strong-willed, it is possible they clashed in the final analysis. According to friends, despite her sureness in her own findings and her husband’s unwavering support, her professor’s critique was terribly painful. She chose to abandon her thesis at the writing stage, having drafted all but the first and last chapters, and she moved on with her life.

From Budapest via Chicago

Hungarian-born Paula Foster (née Hirsch) and her sister were the only members of their family to survive the holocaust. The girls felt compelled to lie about their ages so as to seem older and escape the arbitrary fate of Jewish children too young to be useful to Nazi tyranny. Following World War II, Hirsch and her sister emigrated together to the United States. While her sister aimed for a career as a pianist, Hirsch pursued academic studies, enrolling by the early 1950s as a doctoral student at Chicago’s Northwestern University. A fortuitous meeting with a Ugandan student led to her first welcome in Acholiland. (The student was Martin Aliker, later one of Uganda’s most prominent dental surgeons and businessmen and the first Chancellor of Gulu University, 2004-2014.) Four days after arriving in Gulu in December 1954, she could hardly believe her luck that she was already living in a homestead with the student’s family outside of town. And so commenced her field study.

While in Uganda she met and married Philip Foster, a British education officer who was one of the first teachers at Sir Samuel Baker School. Philip became a professor of comparative education and the couple raised two sons in the United States and Australia. It was a happy marriage that lasted for the rest of their lives. She died in 1997 at the age of 67; her husband died in 2008.

An Undercurrent of Worries

In the field, Foster was readily included in Acholi community activities. She moved with ease socially and was by all accounts popular. Until her departure in 1958 she lived with the extended families of chiefs and controlled her own transport. Her method thus allowed for a kind of dependency that was socially acceptable, even necessary, and an important element of practical independence.

However, she did encounter two particular challenges. First, how could she reconcile an Acholi discourse of abundant land, while hearing on multiple occasions and in different places Acholis’ real fears about land being overtaken by outsiders, possibly with the connivance of Acholi leaders? Second, how could she as a light-skinned person presumed to be British—a ‘European’—grapple with recurring suspicions about her own nature and purpose?

I do not think these challenges were ever resolved in her work nor could they be, especially at that time under colonialism and also under the then-prevailing constraints of anthropology as a discipline. The land issues she encountered, cryptically noted but without follow-up in her papers, suggest painful inequalities in society and with the researcher as a foreigner in a position of relative privilege. Bringing her experiences and evidence to light, however, makes clear that Acholi fears for their land are not new and not simply the result of the LRA war.

The discourse of plentiful land was one she apparently heard from elder men, her main expert sources. The discourse also seems to have been compelling to her as a scholar because it fit with anthropological theories popular in that era, theories of structural functionalism that tended to overlook frictions as well as the presence and power of the colonial state. An example of the land discourse occurred early in Foster’s stay in Acholiland. According to her interview notes, a longtime rwot [chief] told her, ‘You know, land here is not important. No trouble about that. Here money isn’t important. Here we count in cattle’ (Box VI, folder Ae).

Similar ideas are then echoed in her thesis drafts about Acholi marriage. She wrote, for example, ‘The independence of a new house is assured by the gift of land to the new couple. All Acholi women have a claim to the land that lies directly behind their houses’ (Box II, Ka). And: ‘Women have complete charge of their homes and fields’ (Box XII, J11). Noting an Acholi population of 250,000—the precise year of the figure is not given—Foster further drafted, ‘There is a relatively good supply of land limited only by the capacity to use it. [There are] no land disputes except on an interchiefdom basis. Since land rights are defined on a communal basis, land disputes occurs [sic] only on these levels. Very infrequent, due to availability of land’ (Box IX, A.J./Kb).

After such assurances of plentiful land and its orderly allocation, it is therefore surprising for a reader of her field notes to come upon frequent examples of worries, even dread about land. These concerns and anxieties, which took many forms, exposed fissures within Acholi society under pax Britannia. They also suggest people’s awareness of their place in the wider world and the potentially harmful effects of geopolitical trends.

A brief conversation at a funeral, for example, offers a glimpse of these concerns as part of historical memory and of potential future violence in some uncertain, possibly distant, locale. A man whom Foster met discussedhis life as a soldier for three years in the King’s African Rifles. The ‘young queen’ [Elizabeth], he said, ‘will want to have some more land and she will get everybody to fight for her.’ While themoney he had earned as a soldier was not worth it, he would probably haveto go to war again, he said (Box X, Bc).

Another time, her assistant worriedly told her that people wanted to know why she was mapping the fields. ‘Ojat and Ojul are asking why I made a map and saying there will be war if I tried to take their land,’ she wrote, wondering why the pair did not ask her directly what she was doing: Were they afraid of her? Their concern grew out of tensions surrounding the upcoming elections as well as the civil war in nearby Sudan, she supposed (Box VI, De).

People also wondered what anthropologist F. K. Girling, her predecessor in the region, might be writing about Acholi society: whether it could leave them somehow vulnerable. His book The Acholi of Uganda was not yet published; that would happen in 1960. It seems individuals missed him and also wanted Foster to explain his whereabouts as well as the status of his book about them (Box X, Bc, Bd, and Hc). She apparently did not know Girling personally and had no answers. She wrote, ‘They say Girling has gotten lost and will probably never come back to Acholi’ (Box X, Bc). Another time, a teacher grilled her: Had the government sent her, has Girling written his book yet? Girling should have done it by now. If it was a bad book that must be why Foster was sent here to write another one (Box X, Bd). She also had a tense interrogation from Acholi political leaders who questioned her business and were suspicious of the truth of her claims when other white people had exploited them. When Foster asked them to trust her, they said Girling came to do what she did and nearly got killed—why or by whom is not noted (Box VI, De). Foster thought they were lying about Girling. She further reasoned that they did not understand the difference between a protectorate and a colony and this was why they feared their land being taken (Box VI, De).

Further contradicting the discourse of abundant land, Foster also met people living near Gulu town who still suffered from their displacement four decades earlier from the sleeping sickness-prone region that subsequently became Murchison Falls National Park. A son of a rwot told her, ‘It is very bad luck not to have enough land. It gives great sorrow to the people. Just look at the children, see how weak they are. There is no milk to feed them….’ His clansmen were no longer allowed to hunt or fish even though there were plenty of fish in the Nile, he said. People explained to Foster that they could not even move away from here because other areas were already too crowded: ‘The people have little land there, too’ owing to a government rule that those with cattle should only graze cattle on their own land and not exceed the boundaries.

Then the rwot’s son asked, ‘Do the British govern America? Why can the Americans govern themselves and the Africans can’t? Why should the Africans have a government over them?’ Foster wrote, ‘Then they asked whether there were many people [in America] and did they have enough land’ (Box X, Bd). Her answer is not documented.

A Generational Divide

Sometimes young and older men confronted her with their belief that she was a government spy sent to Acholi to take away their land (Box VI, De; Box XI, D n2; Box X, Bd).Once, probably in 1956—she rarely wrote the year in notes—people in one community refused to speak with her, accusing her of being a spy who came to steal their land. To break the tension, Foster agreed: Yes, she came around every night with a big sack and hauled away their land. The joke seems to have calmed them. She nonetheless felt angry about the scrutiny and at answering the same questions again and again about who she was and what she was doing (Box XI, D n2).

In the same encounter, in what suggests a painful division between young and older male generations over issues of land, masculinity, and history, a young man publicly interrogated her and the elders with whom she was chatting. He bitterly recounted a period of disarmament in which the muno (Europeans) tricked Acholi into giving up their weapons that were subsequently burned. (If he meant the wake of the 1911-12 Lamogi rebellion, it is not clear.) ‘This’—her presence—the young man insisted, was the same problem: She must be working on behalf of the District Commissioner. Turning to the elders present, the young man said they ‘always thought they were so smart. But look what happened to them’ after disarmament. Now the land is being taken away from them. Their children will be poor, homeless men, he predicted. ‘If the ludito [elders] were so smart, then why isn’t Lasto Obol still the chief, why did they put in a commoner to be Rwot, why are there national parks? Have you asked [Foster] about those things?’ (Box XI, D n2).

Surprisingly perhaps for readers, but as testament to Foster’s positive attitude, the encounter ended on a high note and she was invited back (Box XI, Dg11).

The ‘War of God’ and Acholi Suspicions

When a Langi religious group of striking peculiarity tried to set up their homestead a few miles from Gulu town in the mid-1950s, neighbours speculated that the members’ true motive was less religious than land-based. As one neighbour claimed, since the government planned to give land to every Acholi, he hoped this group—which called itself Mony pa Lubanga (War of God)—was not there to take land; he added his hope that Europeans and Asians would not get land either (Box VI, Bd).

Most of the few dozen young converts—none Acholi—were under 25 years old. Their round compound had 14 houses as well as a simple church, sitting room, and bicycle shed (Box VI, Bd). Detective-style, Foster tried to fathom Mony pa Lubanga. The clues were maddeningly difficult to parse. Aside from their strange martial-like tendencies—marching, group calisthenics—their religious service was identical to Protestant ones. Neighbours had once seen a flag, but the group’s leader insisted that it was nothing special, bearing only the words Mony pa Lubanga (Box VI, Ad).

After interviewing the leader, Foster’s assistant and his friend opined that the group was crazy but harmless. Still, she could not understand why they left behind fields and cattle in Lango to settle more than a hundred miles away (Box VI, Bd). Others agreed among themselves that religion was but a pretext (Box XI, ac).Although Foster was not able to answer the question of why they came—or why and when they left—the community dealt with Mony pa Lubanga by effectively freezing them out. The group was treated as ‘guests’ rather than kin, Foster wrote, meaning that they were not allowed to disperse, their homestead was but temporary, and they were not given any opportunities in the community (Box VIII, Jd). One can presume they departed before long.

Defending ‘with bare hands’

Finally, Foster’s research suggests a foreshadowing of the Apaa crisis of 2015 in which Acholi women tried desperately to defend against land appropriation by figures including government. Describing a controversy in the mid-1950s over what sounds like the establishment of two coffee farms, Foster learned that plans were announced to the Acholi community without their consultation or input. According to one man she spoke with, the District Commissioner and the Agricultural Officer had already conferred with the Acholi Standing Committee and the rwodi [chiefs] and the resolution was passed; therefore it was a done deal. According to this man, women ‘were the most militant against the farm,’ saying they would rather work the land with their bare hands from morning till night than use supposedly labour-saving machines and lose ‘the land of their fathers’ (Box VI, Ae).

The farm managers or operators—whether British, Acholi, or Indian is not specified—tried to persuade the women that they would not have to work so hard at farming because machines (perhaps tractors) would help them. Still the women refused. As Foster wrote, no one wanted to accept the planting of coffee despite the potential increase in money, if it meant losing their land.

‘It is a cruel way of introducing these things,’ her interlocutor told her. ‘People should have been consulted first. Even though the government can only lease the land, it would be as if they owned it’ (Box XI, B g14). Alas, no further details are available.

Conclusion

Acholi concerns about land alienation go back to at least the 1950s. Acholi fears for their land are therefore not new and not simply the result of the LRA war. F.K. Girling, in whose shadow Foster worked, had written that Acholiland was underpopulated—there was plenty of land—perhaps because he focused on population density rather than the politics of land. Indeed in Foster’s own written drafts for her thesis she adhered to this line of reasoning. Therefore it is all the more striking to find that people were so sensitive about foreigners wanting to take land. Acholis were also vulnerable to fellow Acholis who did not consult them on decisions about land that affected their lives, their future, and their ancestors.

Photos by Paula Hirsch Foster

(Photos, undated: Paula Hirsch Foster; courtesy of Boston University Paula Hirsch Foster Collection)

(Photo courtesy of Boston University Paula Hirsch Foster Collection)

Notes on Contributors

Julia Vorhölter studied social anthropology and political science at Hamburg University and holds a PhD in anthropology from Göttingen University. She is currently employed as a lecturer and post-doc researcher at the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology in Göttingen. Her ethnographic research experiences include field studies in Uganda, South Africa and Niger. Much of her work has concentrated on dynamics and perceptions of socio-cultural change in Sub-Saharan Africa, including changes in gender and generational relations and changes in the political landscape due to armed conflicts, foreign induced reforms and development interventions. Her most recent project focuses on contemporary discourses on mental health and emerging forms of (psycho)therapy in East Africa, especially Uganda.

Contact: jvorhoe@gwdg.de

Sam Dubal received his Ph.D. in medical anthropology from the University of California-Berkeley and the University of California-San Francisco in 2015. He is the author of a forthcoming book, entitled Against Humanity, based on his doctoral dissertation research with former Lord’s Resistance Army rebels. He is concurrently earning his M.D. at Harvard Medical School and plans to train as a trauma surgeon.

Contact: sambdubal[at]gmail.com

Ina Rehema Jahn completed a BA in Social Anthropology and Development Studies at SOAS, University of London, and is a graduate of the Erasmus Mundus Master in Migration and Intercultural Relations taught by University of Oldenburg, University of Stavanger, Makerere University Kampala and the University of the Witwatersrand. An anthropologist at heart, her research interests pertain to the study of forced migration, borderlands, cosmologies and concepts of belonging with a particular focus on East Africa. She is currently with the Land, Property and Reparations Division of the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) in Geneva, engaging with land restitution and reparations programmes in a range of post-conflict contexts.

Contact: Ina.R.Jahn[at]gmail.com; ijahn[at]iom.int

Anne Wermbter is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany. She currently teaches at the Institute of Anthropology, Universität Leipzig. She worked as a lecturer at the Institute of Cultural and Social Anthropology, University of Cologne and at the Freie Universität Berlin. She carried out long-term ethnographic fieldwork in Uganda, Austria and Benin. Her main research interests are in the field of anthropology of violence and conflict, natural disasters, refugees and migration. Her current research is concerned with matters of memory, coping strategies, gender relations and mental health in post-conflict and post-disaster situations.

Contact: annewermbter[at]yahoo.de

Clara Himmelheber is the head of African Collections at the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum – Cultures of the World, Cologne (Germany). She is also a lecturer for Museum Anthropology at the University of Cologne. She studied African Studies, Anthropology and Art History at the University of Cologne. For her MA in Anthropology she carried out ethnographic field research in Namibia, for her PhD. in African Studies she conducted fieldwork in Uganda. She has been author of several publications and curator or co-curator of numerous exhibitions, e.g. ‘Namibia – Germany: A Shared/ Divided History. Resistance, Violence, Memory’ at the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum and the German Historical Museum Berlin and the permanent exhibition ‘People in their Worlds’ at the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum. Currently she is project manager of the special exhibition ‘Pilgrimage – Longing for Bliss?’ at the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum.

Contact: clara.himmelheber[at]stadt-koeln.de

Martha Lagace is a doctoral student in the Anthropology programme of Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. She earned her Master of Liberal Arts degree at Harvard University and her Bachelor’s degree at Simmons College, Boston. She has recently completed two years of dissertation fieldwork in post-war Gulu, Uganda, studying the history and social life of transportation during and after the 1986-2008 civil war, focusing on the rise of boda-boda motorcycle taxis. Martha has also conducted ethnographic research in Rwanda on memorialising the 1994 genocide. She and Dr. Jens Meierhenrich published a photo essay on this topic in the journal Humanity.

Contact: mlagace[at]bu.edu