Ina Rehema Jahn

African Centre for Migration and Society, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Abstract

Since the end of the conflict in Acholiland, northern Uganda, development actors increasingly embark on economic reconstruction and rehabilitation projects in former IDP camp sites. Yet, all these sites contain multitudes of graves as a burial back at home was greatly obstructed during the period of forced encampment. For many Acholi, a burial away from home is however widely believed to aggrieve the spirits of the dead, whose bones are said to lie in the ‘wrong soil’. Former camp residents have attributed misfortunes and illness to these bones left behind in the camps. Since the first closures of IDP camps in northern Uganda, the need to move graves from former camp sites back home has thus occupied the imagination of many returnees, and reburials have become a common practice. At the same time bones and graves left behind literally come to the surface in the context of reconstruction projects in former camp sites. Drawing from the example of a donor-funded infrastructure project in former Pabbo IDP camp, this article highlights both the material and cosmological implications of dealing with bones and graves that have been left behind in these sites. It argues that while reburials are intimately linked to questions of local cosmology and efforts to reconstitute a sense of belonging in the post-conflict phase, the practice also becomes subject to political stakes of development and government actors with potentially unsettling cosmological consequences. Without understanding both material and cosmological concerns of former displaced populations regarding graves in the ‘wrong soil’ and their appropriate treatment, development initiatives in former camps in Northern Uganda hence run the risk of causing renewed social and cosmological disorder.

Since the 2006 Cessation of Hostilities Agreement, which marked an inconclusive end to war between the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and the Ugandan government, the majority of the forcibly displaced have returned to their former homes. However, the violent disruptions of social, political and economic life which marked the two decade long conflict remain etched in collective memory and linger on as returnees attempt to remake homes and reorder lives. Among the remnants of war are also the physical remains of those who died in the displacement camps and were buried away from ancestral or marital land, a situation commonly described by former camp inhabitants as ‘bones in the wrong soil’ (congo i ngom ma pe tye kakare). Death was a daily occurrence throughout the period of forced encampment, conditions of which have been described as amounting to ‘social torture’ evidenced in ‘widespread violation, dread, disorientation, dependency, debilitation and humiliations (…) perpetrated on a mass rather than individual scale’ (Dolan 2009: 2). The harrowing camp conditions caused excess mortality levels classified as highest humanitarian emergency (Branch 2012: 89, WHO & MOH 2005) while the camps themselves also ‘soon became magnets of fighting’ (Finnström 2008: 136). Destitution and death were so omnipresent that a strong local narrative emerged which framed the camps as the implicit means to control, dominate and even ‘exterminate’ the Acholi population (Finnström 2008: 144).

In the context of such intense structural violence perpetrated against the majority of the Acholi population, cultural and social agency became severely diminished while cosmological orders were also subject to new negotiations. In Acholiland, where the dead are customarily given a burial at home and graves are sacred places intimately lived with on one’s homestead, culturally appropriate recognition of the many occurring deaths often became impossible. Official restrictions on movement and the lack of income both heavily inhibited the transport of the remains back home as well as the customary institution of funeral rites. In Acholiland, improper burials are however thought to greatly aggrieve the spirits of the dead who as a result can cause misfortune, illness and even death among their surviving relatives and the wider clan (Baines 2010), spreading cosmological disorder and upheaval. Since the end of the conflict, many bereaved families have therefore organised reburials from camp sites to their former homesteads in order to appease the spirit of their dead relatives and to reconstitute a sense of belonging with their land. Reburials in post-conflict Acholiland thus acquire their meaning in the relation to prevalent cosmologies tied to notions of place and belonging and the shared experience of structural, decade-long violence.

The emergence of reburials in post-conflict Acholiland also coincides with rapidly increasing business opportunities and land commercialisation in the former camp sites, which are purposefully developed into larger urban centres (Whyte et al. 2014). Since the end of the conflict, the Ugandan government has exerted ‘highly public pressure (…) for the opening up of Northern Uganda for “development”’ (Atkinson 2009: 2) by incentivising large scale infrastructure and economic rehabilitation projects in the area. As highlighted by Whyte and colleagues (Whyte et al. 2014), this drive for development is underpinned by the logic of subtraction: to clear the way for concerted development intervention and economic reconstruction, former camps need be cleared from both the remaining displaced populations as well as the dead bodies they left in the ground.

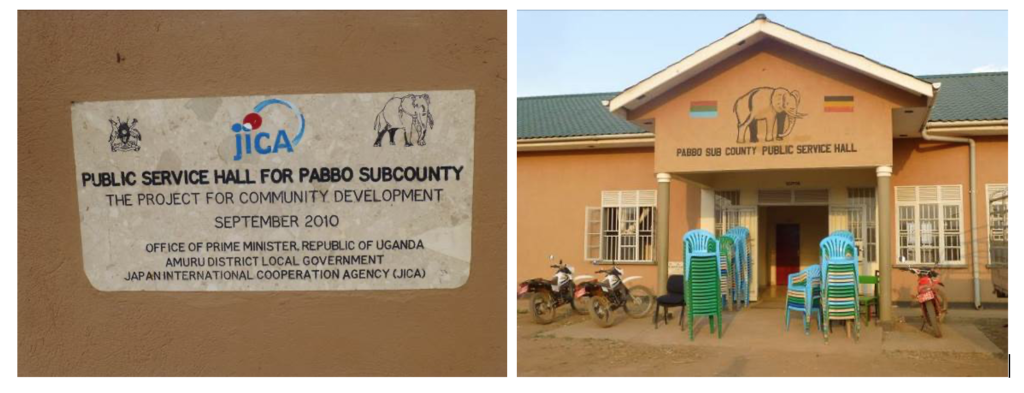

Local cosmological idioms circumscribing the engagement with the spirit world – of significant importance to many Acholi – therefore become entangled with development approaches which are often grounded in materialist concerns that fundamentally exclude the cosmological domain. As a consequence, family-level negotiations over the reburial of their dead have become part and parcel of post-war reconstruction efforts. The potential consequences of these processes are highlighted by the construction of a sub-county hall in former Pabbo IDP camp funded by the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) in 2009, following the request for support by the sub-county leadership. The construction of the hall provoked widespread anxiety and concern among Pabbo’s residents, and led the agency to funding both exhumations from the construction site as well as reburials in returnee villages. Many of the affected families experienced these reburials as a forceful violation of their cosmological imaginations with unsettling consequences, long outlasting the presence of JICA.

This article aims to situate reburials in the context of post-conflict development and reconstruction initiatives and their politics in former Pabbo camp. Based on six weeks of fieldwork in early 2013, the case of JICA’s involvement is used as a lens to understand how bodies and bones ‘in the wrong soil’ are not only part and parcel of local negotiations of the meaning of home and belonging in the wake of return, but also and simultaneously the substance of post-conflict politics in the former camp sites such as Pabbo. It is hence important to return the debate on post-war belonging and reconstruction to a discussion of local cosmological idioms and concerns and shift away from analyses grounded in predominantly materialistic worldviews and concerns.

Dying and Burying in Northern Uganda’s IDP Camps

All over the world, ‘burials reflect upon the complicated relationships between humans, land and belonging’ (Núñez & Wheeler 2012: 215). In Acholiland, the connection between the living, the dead, and family land is particularly strong. For most Acholi, death indicates not a separation but a transformation of relations between the realm of the dead and the living (Mbiti 1969, Odoki 1997, p’Bitek 1971), and the ancestors play a significant role in the affairs of the living. It is through a properly performed burial, which prominently includes being buried at home, that ‘the deceased person is initiated into the divine lives of the ancestors, who are believed to be the founders and the guardians of society’ (Odoki 1997: 2). If someone dies a ‘good death’, the spirit of the deceased will become tipu maleng – a ‘pure ancestor’ (Behrend 1999: 23) or a ‘holy spirit’ blessing or protecting the descendants. But when proper funeral rites have not been conducted, or a burial has taken place in an unfamiliar location or not at all, the spirit of the deceased can become a tipu marac (‘evil/bad spirit’ or ‘aggrieved ancestor’) or even cen (‘vengeful ghost’) that haunts the relatives responsible for the improper burial, and also the wider clan.

The impact of forced encampment, obstructing a proper ritualised burial at home, greatly disrupted the transformative and regenerative process normally brought about by an honourable burial. Due to this failure to create order vis-à-vis death, ‘bad death spread throughout the landscape and social order’ (Jahn & Wilhelm-Solomon 2015: 188) and daily surroundings became imbued with tipu marac. Dead bodies interred in ‘foreign’ IDP camp soil demanded active management and containment from their families and clans.

It is in this context that Acholiland has seen the widespread emergence of reburials from former camp sites to pre-displacement areas of residence in the wake of return. These reburials in the post-encampment phase are indicative of a cosmological idiom which circumscribes home as the place where the ancestral collective is anchored. AsFinnström has observed in his study of healing ceremonies during the war in Acholiland, the emergence of reburial similarly presents the ‘process of socialization in which the victim is incorporated and reconciled with the community of the living and the dead…The traumatic experience is socially deconstructed’ (Finnström 2008: 161). With a reburial in the place of residence prior to encampment, and a return of the spirit to where it belongs, the deceased can finally join the ancestral collective (Hertz 1960: 54) and is incorporated and reconciled with the community of the living and the dead.

For the surviving relatives, the reburial itself is not only emotionally charged but also very costly. The whole process, often spread over several days, demands the sacrifice of a goat or sheep, men to do the work of exhuming and reburying, the transport of the remains, payment of a traditional healer or spirit medium (ajwaka) who will call home the spirit of the dead, as well as food and drink for the larger family and clan to gather and celebrate.

Development Projects in Former Camp Sites: Encountering ‘Bones in the Wrong Soil’

Usually a solely community-regulated affair, reburials and graves remaining in former camp sites have also become of increasing concern to international development agencies. The resulting entanglement of material concerns and cosmological imaginations is exemplified by a recent development project implemented in Pabbo, formerly the largest IDP camp in northern Uganda with a population of 65,000 people at the height of displacement in 2004 (Dolan 2009: 108). Since the official camp closure in 2010, Pabbo has developed into a thriving urban centre on the strategically important route connecting Kampala and South Sudan. Mergelsberg (2012: 67) describes the effects of Pabbo’s post war economic boom: ‘…the IDP camp was turning into a permanent semi-urban space… Previously one of the remotest areas in Uganda, Pabbo suddenly found itself in the middle of a border region of growing importance.’

Today, traces of the camp structure are difficult to spot by an untrained eye and economic interest in the area is continuously increasing. Pabbo trading centre now boasts a primary and secondary school, a Health Centre IV, a very active market place, modern government infrastructure, and many video halls and bars. The existing road connecting Pabbo and Gulu has recently been tarmaced with funding from World Bank, which has further facilitated the regional and cross-border flow of people and goods. Having been bestowed the status of Town Board by the Ministries of Local Government and of Finance and the district government, Pabbo is now officially recognized as an emerging urban centre and receives financial support for the systematic planning of urban development (Whyte et al. 2014).

The upgrading of the former camp to the status of Town Board and the prospect of further elevation to Town Council have resulted in the division of government and family land into plots to be privately sold and developed, thereby acquiring new value and commercial significance. In due course, bones and graves which had so far remained in the former camp site have become a hindrance to the wider development and post-war reconstruction agenda actively pursued by private landowners, local leadership, NGOs and government officials in the area. Among Pabbo’s political leadership the remaining graves are widely framed as inhibiting economic commodification and obstructing the ‘dreams of development and proper urbanization [which have taken hold] in the former camp sites’ (Whyte et al. 2013). As one of Pabbo’s parish chiefs stated evocatively, ‘business and unknown graves do not go together’ (Pabbo Trading Centre, 14 January 2013). Building on a grave is widely perceived as severely disrespectful towards the dead, and is likely to cause great spiritual harm to those who attempt doing so. In the words of a private landowner in Pabbo, ‘it is problematic to build on graves as the spirit of the dead will complain that you are stepping on him, suffocating him. It will invite trouble to your family’ (Pabbo Trading Centre, 01 February 2013).

In discussing the presence of graves in post-conflict Pabbo and the issues they raise, a member of the newly formed Pabbo Trading Centre Landowner Association explained that ‘we advise people to hurry up in exhuming bones in order to free up opportunities for development’ (Pabbo Trading Centre, 01 February 2013). On frequent occasions, the Association has facilitated the bringing together of families and landowners to avoid open conflict and smoothly arrange for exhumations:

We, as landowners, are very interested in removing the graves but families are delaying us. It is a very common problem among us landowners in the trading centre, and at the meetings with the Association it is a very frequent issue that we discuss…If you want to do development, you must seriously pressurise the families into reburying quickly. In some cases, members have even subsidised reburials in order to hurry up the process. (Member of Pabbo Trading Centre Landowner Association, Pabbo Trading Centre, 01 February 2013)

These dynamics underline the argument that development agendas in former IDP sites are underpinned by the logic of subtraction; that is the removal of both the last remaining displaced persons as well as the dead who were interred in the camp during the conflict. In the words of Whyte et al. (2014: 605): ‘The transformation of the IDP camps back to trading centres was a matter of subtraction. The displaced people had to be re-placed in their rural homes; thousands of their huts had to be demolished…and the multitude of graves had to be removed and put where they belonged.’

In this context of emerging urbanism and increasing land commercialisation, Pabbo’s sub-county leadership was approached by the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA), a valued development cooperation partner, with the offer to construct a new sub-county multi-purpose hall as outlined in the sub-county’s latest development plan.

In an enthusiastic response, the sub-county officials allocated a large plot of centrally located land to JICA for construction purposes. However, the construction planners soon encountered numerous bones and graves in the allocated land, which delayed the execution of the project and ultimately led the agency to fund both exhumations from the construction site as well as reburials in returnee villages.

It is important to note that reburials did not fall under JICA’s mandate of supporting the rehabilitation and reconstruction of physical infrastructure. As such, JICA found itself under pressure to justify to its stakeholders why they had proven to be flexible and funded reburial ceremonies. In the May 2010 newsletter of JICA’s Gulu Office, the intervention was framed as an act of respect for Acholi culture but also as a decision firmly based on an economic cost-benefit analysis:

Since the sub-county had also insufficient budget, JICA was requested to provide assistance by providing the funds for sheep and goats to facilitate the rituals. However, it should be noted that such assistance by JICA is not part of JICA’s major assistance program, and that this was a way of speeding up the constructing process. Partly, the activity was funded by JICA because of the respect it holds for the culture of the Acholi community. (JICA 2010: 2)

In this sense, the cosmological dimension was largely bypassed: in an apparent commodification of ritual action, JICA presented its decision to fund the reburials as the most effective method to swiftly get the bones out of the land. Not only were the remaining graves in the area framed as an obstacle to development, but JICA actually took an active role to ‘get rid’ of the obstacle by paying for the reburial ceremonies to take place.

Affected families were given one week from the 19th to the 26th of February 2010 to exhume their dead from the construction site. During this period 249 bodies were claimed by 92 different families, and taken home for reburial. On each day, a sheep was slaughtered in the presence of a cultural leader, who then ensured the sprinkling of its chyme (wee) into each exhumed grave to bless the spirit of the deceased, before the bodies were transported to their reburial sites. As some families lived very far away and transport costs were not covered by the JICA budget, several graves remained unclaimed. In a few cases, relatives living closer to Pabbo took on the task to exhume the bodies, but eight families were unable to find an alternative arrangement. These remaining graves were in due course levelled by the construction workers.

The completed Sub-county Hall in Pabbo Trading Centre, February 2013

(Photos: Ina Rehema Jahn)

The Politics of Donor-funded Reburials in Pabbo

The government-initiated exhumations and reburials funded by JICA were widely experienced as a disruptive experience among inhabitants of Pabbo. Many residents perceived them to be a factory-like process focused on little else than an efficient and speedy subtraction of graves from the construction site. While some of the affected families referred to the JICA´s funding of the exercise as an example of compassionate development assistance, many others experienced the speedy, large-scale exhumations and reburials as a forceful violation of cosmological imaginations. A closer examination of the multiple and often astoundingly contrasting narratives circulating in Pabbo regarding the JICA-funded exhumations and reburials helps to understand how graves and bones became potent agents in local politics through the trope of reconstruction and development.

The local leadership in charge of managing the reburial exercise on the ground was largely adamant that only a few elderly people had initially resisted the exhumation and reburial plans. The government stance disseminated throughout was that the sub-county needed to develop, and that development cannot be delayed by resistance to the construction plans. As one of Pabbo’s civil servants put it, ‘the law says that development comes first (…) when development is taking place, everything must make way’ (former Sub-county Chief, Gulu, 10 February 2013). According to the sub-county employee tasked with the direct oversight of the reburials, most affected families ultimately agreed to the reburials as long as assistance in the form of goats, sheep, food and drinks would be provided (Parish Chief, Pabbo Trading Centre, 14 January 2013). It is unclear exactly how many animals JICA agreed to provide, but many families seem to have assumed that there would be one for each home.

Before the reburials, JICA had also invested heavily in sensitisation exercises for the local population. The main channel to disseminate information was JICA’s weekly radio talk show named Dongo Lobo Acholi (‘Development of Acholi Land’) on MEGA FM, the major radio station in nearby Gulu Town. Among local government officials, JICA also paid Pabbo’s Rwot Moo, the most senior cultural leader on community level, to come on air and disseminate information regarding the exhumations and reburials to his constituency. The JICA Gulu Office May 2010 Newsletter summarises his radio visit as follows:

On Feb 24, His Highness Zaccheus Acaye was invited as the chief guest on the radio show. He was to give his view on the exhuming of bodies in Pabbo in his capacity as the cultural leader of the area (…) [ H]e emphasized the following:

Now that people are returning to their villages, it is important not only as a human thing to do but also in accordance with the dictates of the Acholi culture that the relatives do not leave the bodies of their loved ones in a foreign land. He said that since the people are now going back to their ancestral homes, it is also cultural enough to take with them the remains of their loved ones to their ancestral resting places (…) [H]e requested all the people who had relatives buried in Pabbo Sub-County land to take advantage of the assistance rendered by JICA and the sub-county to relocate the remains of their loved ones within the stipulated time period (…) in his conclusion, His Highness appreciated those who responded positively for the function earlier and encouraged others to do the same. He further on behalf of the people thanked and appreciated JICA for respecting the culture of Acholi by funding the requirements for ritual activities that was not in their budget line.

(JICA 2010: 2)

Significantly, JICA officials feared that families could take material advantage of the exhumation and reburial exercise. This was not entirely unfounded, as earlier USAID budget allocations for cleansing ceremonies in areas across northern Uganda, where bones were found, had previously gone missing. As one of JICA’s field officers explained, ‘we were worried that people would take the material benefits offered by JICA and then not dispose of the body correctly. So we were checking thoroughly whether any body was dumped elsewhere than home’ (JICA Field Officer, Gulu, 04 February 2013). Seeing the importance of an appropriate treatment of dead bodies, the preoccupation with the potential misuse of funds nonetheless points to a potential disconnect from prevailing cosmological concerns in Pabbo. Instead, the institutional focus squarely remained on creating measurable, added infrastructural value to boost local government capacity in as short a time frame as possible. As such, as Jones has stated in his examination of the durability of Pentecostal churches vis-à-vis the brief after-lives of local development interventions in Teso, eastern Uganda, the language and objective of technocratic development actors ‘remained distant from people´s landscape of interpretations that made up the place’ (Jones 2013: 88).

In contrast to the fear of JICA officials, and maybe as testament to their misunderstanding of the cosmological significance of reburials, all exhumed bodies were in fact reburied. Nonetheless, many of the affected families described the exercise as highly unsettling and in some cases even as re-traumatising. Apart from widespread cynicism marked by a perception that the JICA intervention had primarily benefited the sub-county leadership and a generalised sense of discontent with perceived politics of patronage, many stressed the lack of time and adequate resources as main causes of the cosmological upheaval caused by the JICA-funded exhumations and reburials.

Many of those who were pressured into the reburials claimed to have received only a half, a quarter or no sacrifice animal at all, which, in the absence of further financial resources, prevented the proper ritualisation of reburial. In the words of a family caught up in the reburial exercise, ‘these weren’t decent reburials – but an incomplete process instead because important items were missing. Such a rushed reburial can really come to haunt families and cause great misfortune’ (former Camp Leader, Pabbo Trading Centre, 15 January 2013). Even the local Parish Chief and focal person for JICA explained that ‘some families were not happy with exhumations. Goats that we gave to parishes were not enough to cater for all families, and the families had to cover transport costs themselves, which meant that it became a financial challenge for some’ (Parish Chief, Pabbo Sub-county, 07 February 2013). The head of local government in turn rationalised the lack of fully catering to transport needs by stating that ‘it is crucial that the families also contribute something, because if everything is funded by Japanese it damages our rituals and makes us lose our traditions’ (LC3, Pabbo Trading Centre, 14 January 2013).

The Reburial Process as a Source of Cosmological Upheaval

The experiences of the families who had to rebury under the JICA initiative highlight the complex contestations entangled with the JICA-funded exhumations and reburial exercise. Okot’s family reburied seven children (including twins, who are imbued with jok, or particularly strong spirits warranting special treatment after death) in due course of the JICA-funded construction project. The family’s biggest concern pertained to the fact that contrary to public promises, they had not received a single goat to use as a sacrifice. Instead, one goat had been given to the whole parish in which more than forty families had to rebury relatives that day. This one goatwas slaughtered and consumed by those who exhumed the bodies and carried them home, and therefore could not be utilised for ritual purposes.

At the time, Okot and his family were also embroiled in conflict over access to their ancestral land. Without time to come to an interim agreement for the reburials of their deceased family members, they were unable to bury the exhumed bodies, as Okot expressed it, ‘in the soil where our ancestors are resting’ (Pabbo Sub-county, 06 February 2013). As he continued to explain, this has caused great consternation and worry in the family: ‘That is our land. We wanted to re-bury our loved ones there (…) I don’t know yet if the spirits will complain about not being brought to their proper home – they may complain because they are supposed to rest on our ancestral land, where the grandparents are.’

In drawing attention to the missing resources needed for a proper reburial, Okot emphasised the widespread rumours that the JICA-funded development intervention had primarily benefited the sub-county leadership. After all, he maintained, none of the material supposedly purchased by the additional JICA budget earmarked for the exhumations and reburials ultimately reached those it had been intended for. Okot’s wife evocatively recounted what she perceived to be the direct consequences of the hurried and improper reburials the family had been pressured into:

The sub-county leadership told us that because of construction of the new sub-county hall by JICA, we need to exhume our loved ones from the area. They promised us that a sheep will be slaughtered to use its wee in exhuming. I didn’t see any of the sheep’s wee, and neither were there any goats that had been promised by the political leadership. My twins were supposed to be reburied with wee from a sheep, but there was nothing there, and this has caused us big problems. (Pabbo Sub-county, 09 February 2013)

As a result of the rushed reburials conducted with very limited resources, she continued wearily, the spirits of the reburied twins are now disturbing her remaining children. While ‘before the forced exhumation, we didn’t feel anything with their spirits, it has started since we exhumed because the Acholi traditional rituals were not done (…) My remaining children frequently fall sick, and sometimes even become temporarily blind’ (Pabbo Sub-county, 09 February 2013). Six months after reburial, she resolved to visit an ajwaka who advised her that the twins’ spirits were feeling mistreated and neglected by their family due to their improper reburial, and demanded two goats as a sacrifice from their family. Still trying to gather the financial resources necessary to do so, Okot’s wife strongly condemned the JICA-funded exercise as a whole as ‘they neither gave us any time to prepare for the reburials nor provided the necessary things to make the reburial proper’ (Pabbo Sub-county, 09 February 2013).

Okello’s family was among the many who still lived on sub-county land when JICA’s development initiative was announced in September 2009. They were given a time span of three months to leave the envisaged construction site, and ‘us people had to agree because the land does belong to the sub-county…there was no chance to protest’ (Kal Parish, Pabbo Sub-county, 05 February 2013). In January 2010, Pabbo’s leadership ordered Okello’s family to exhume their left behind graves. The small portion of goat meat provided by government officials on behalf of JICA did not suffice as food for even the immediate family, which forced him to also slaughter some of his chickens to cater for the family’s guests. In his assessment of the JICA exhumations and reburial as experienced by his family, Okello stated that:

We were promised a goat for each grave by the local authorities. But as we came to experience, later on, it came down to a quarter goat (…) I didn’t feel happy because I had to provide chicken to feed the reburial guests, which I had not anticipated at all. It has caused us financial trouble. Everything was so abrupt but an ajwaka and the organisation need money, which I could not organise in the little time given. (Kal Parish, Pabbo Sub-county, 05 February 2013)

The family intends to hold another reburial celebration once they can afford to purchase a goat. Yet he counts himself lucky as his clan brother, who was also called to exhume and rebury bones from the sub-county grounds, failed to locate his two graves before the end of the deadline. The construction did commence regardless, causing the family further grief and concern for the deceased’s spirit.

Reburials and Post-war Development: A Site of Politics

Rupture and dislocation are defining and encompassing experiences inscribed in northern Uganda’s history and the life worlds of its inhabitants, who have lived through more than two decades of war between the LRA and the Ugandan government. In the wake of return from forced displacement, efforts to remake homes and reorder lives have taken centre stage across the region. The return period is also marked by continual anxiety over the unsettled dead who have died and were buried away from home in the displacement camps. Reburials from former camp sites to returnee villages are thus highly expressive of the notion of home and belonging in the aftermath of ‘seriously bad surroundings’ (Finnström 2008: 193). At the same time, ‘dreams of development’ pursued by the Ugandan government and international development actors have changed the landscape of post-conflict northern Uganda and are leading to continued urbanisation and increased commodification of land.

In the context of these post-conflict rehabilitation processes, graves left behind in former camp sites have also become a public concern involving development actors, national and local leadership and private land owners. As illustrated by the JICA-funded exhumation and reburial exercise in Pabbo, reburials are instrumentalised through political stakes of other actors who interact with local cosmologies as material and cosmological concerns become intimately entangled. The case thus highlights the complex and potentially unsettling interstices between local cosmologies, the impacts of conflict and displacement, and the developmental and reconstructive agendas of state and international agencies.

In outlining the contestations surrounding the reburial exercise, this article has aimed to show how different actors have perceived and understood JICA’s development assistance in Pabbo in contrasting ways. JICA employees took a very technocratic stance vis-à-vis the exhumations and reburials; even checking on whether bodies are disposed of correctly and ensuring that no funds were claimed without an actual reburial. The political leadership was primarily concerned with bringing development to sub-county level, sharing the same rationalistic development idiom as JICA. Yet, the JICA-funded exhumations and reburials have been a severely disruptive experience for the individual families affected. The severe consequences are maybe most evocatively reflected in the experience of Okot’s family, who had to hurriedly rebury their jok twins without the promised animal to sacrifice and is now haunted by their aggrieved and restless spirits. This succinctly shows that cosmology is not separate from politics; on the contrary, these contestations over land and bodies become the actual site of politics.

The JICA intervention in post-conflict Pabbo therefore provides a lens into how cosmological idioms produce meaning and value that intersect with and problematises the global rationale of development and its focus on rationalised economic objectives and materialist concerns. Primarily preoccupied with creating measurable, material output and little concern for local interpretation frames, the government-coordinated and JICA-funded exhumations and reburials were thus widely experienced as alienating and potentially harmful by many of those subjected to the intervention. JICA and the local leadership thus remained at a distance from the particular, evolving ways in which life is made sense of in post-conflict Acholiland.

In the meantime, Pabbo and other former camp sites in Northern Uganda continue to develop into emerging urban centres and attract increasing commercial interest. More infrastructure projects are implemented and planned, and the sub-region has become a focus of reconstruction efforts predominantly funded by international donors. As more ‘bones in the wrong soil’ will be encountered and uncovered in due course, it is critical to come to an understanding of what it means to ‘reconstruct’ or ‘develop’ in a context in which reburials are often for most intimately linked to questions of an ever evolving cosmology and belonging.

References

Atkinson, R. F. (2009). ‘Acholiland Next Point of Hostility. The Independent, 7th January 2009. http://www.independent.co.ug/index.php/column/comment/70-comment/452-acholi-land-next-point-of-hostility (accessed 16-08-2014).

Baines, E. (2010). ‘Spirits and Social Reconstruction after Mass Violence: Rethinking Transitional Justice’. African Affairs, 109(436): 409-430.

Behrend, H. (1999). Alice Lakwena & The Holy Spirits: War in Northern Uganda, 1985-97. London: James Currey.

Branch, A. (2012). ‘Humanitarianism, Violence and the Camp in Northern Uganda’. In Bakonyi, J. & B. Bliesemann de Guevara (eds): A Micro-Sociology of Violence:Deciphering Patterns and Dynamics of Collective Violence, London: Routledge: 81-106.

Dolan, C. (2009). Social Torture: The Case of Northern Uganda 1986–2006. New York: Berghahn Books.

Finnström, S. (2008). Living with Bad Surroundings: War, History, and Everyday Moments in Northern Uganda. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Jahn, I.R. & M. Wilhelm-Solomon (2015). ‘Bones in the Wrong Soil’: Reburial, Belonging, and Disinterred Cosmologies in Post-conflict Northern Uganda’. Critical African Studies, 7(2): 182-201.

JICA/Japanese International Cooperation Agency, Gulu Office (2010). Newsletter May 2010. Gulu: JICA.

Jones, B. (2013). ‘The Making of Meaning: Churches, Development Projects and Violence in Eastern Uganda’. Journal of Religion in Africa 43 (1): 74–95.

Kaiser, T. (2008). ‘Social and Ritual Activity In and Out of Place: the ‘Negotiation of Locality’ in a Sudanese Refugee Settlement’. Mobilities, 3(3): 375-395.

Malkki, L. (1995). Purity and Exile: Violence, Memory, and National Cosmology among Hutu Refugees in Tanzania. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Núñez, L. & B. L. Wheeler (2012). ‘Chronicles of Death Out of Place: Management of Migrant Death in Johannesburg’. African Studies, 1(2): 212-233.

Odoki, S. O. (1997). Death Rituals among the Lwos of Uganda: Their Significance for the Theology of Death. Gulu: Gulu Catholic Press.

p’Bitek, O. (1971). Religion of the Central Luo. Nairobi: East African Literature Bureau.

Van Gennep, A. (1960 [1909]). The Rites of Passage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Warner, D. (1994). ‘Voluntary Repatriation and the Meaning of Return to Home: A Critique of Liberal Mathematics’. Journal of Refugee Studies, 7(2/3): 160-174.

WHO/World Health Organisation & MOH/Ministry of Health of Uganda (2005). Health and Mortality Survey among Internally Displaced Persons in Gulu, Kitgum and Pader Districts, Northern Uganda. http://www.who.int/hac/crises/uga/sitreps/ Ugandamortsurvey.pdf (accessed 10-08-2014).

Whyte, S.R., Babiiha, S. M., Mukyala, R. & L. Meinert (2013). ‚Encampment to Emplotment: Land matters in Former IDP Camps’. Journal of Peace and Security Studies, 1: 17-27.

Whyte, S.R., Babiiha, S. M., Mukyala, R. & L. Meinert (2014). ‘Urbanization by Subtraction: The Afterlife of Camps in Northern Uganda’. The Journal of Modern African Studies 52(4): 597-622.